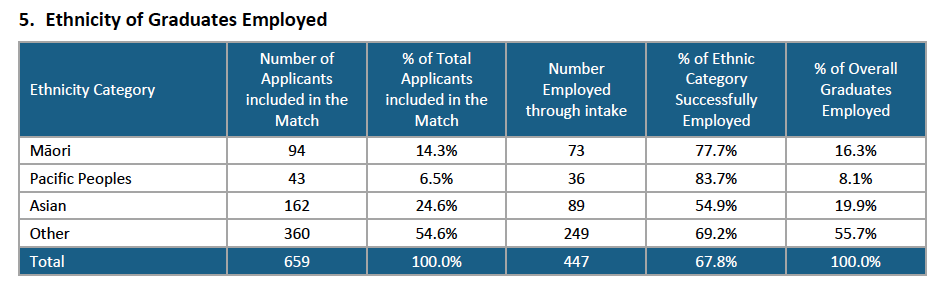

The ACE Nursing Intake Summary Report** for the mid-year intake showed that 447 – just short of 68 per cent of the 659 applicants – received a job offer for a new graduate programme place between July and late October via the ACE job-match process.

When the mid-year pool closed on October 27 there were 190 (28.8%) left in the pool who were still seeking supported new graduate jobs – over a hundred less than the same time last year.

This was the lowest percentage of the mid-year intake still job-hunting into the spring since ACE records began in mid-2013 – and just over a hundred less than the same time last year, when 43 per cent of mid-year applicants were still job-hunting in the spring.

The 51 nurses taken on by mental health and addiction providers for NESP [new entry to specialist practice – mental health and addictions] programmes contributed. The improved mid-year employment rate was also reflected in the findings of the annual mid-year graduate survey undertaken by NETS (Nurse Education in the Tertiary Sector).

According to the ACE report Pacific nurse graduates were proportionately the most successful in getting a job through ACE with 83.7 per cent of the 43 applicants being employed. The next most successful were Māori graduates with 77.7% of the 94 applicants being matched with a job.

The “other” ethnicity category – which includes New Zealanders of European descent – made up just over half of the applicants – 360 (54.6%) and had a job success rate of 69.2%, which was just above the overall job success rate of 67.8 per cent*. Kiwi nurse graduates of Asian ethnicity made up 162 (24.2%) of applicants and had a 54.9% per cent job success rate – the lowest of the four ethnic groupings. (NB to be eligible to apply for a funded NETP [nursing entry to practice] or NESP [new entry to specialist practice – mental health] position through ACE you need to be a New Zealand citizen or hold a permanent/returning resident visa.)

In November 2015 the Health Workforce New Zealand’s (HWNZ) Nursing Governance Taskforce for Nursing set a date of 2028 to meet a goal of significantly increasing the number of Māori nurses so as to better match the proportion of Māori in the population, with the aim of improving access to care and the quality of care for Māori. ACE statistics for the end of 2015 showed 54 per cent of Māori graduates were known to be employed, compared to 50 per cent of non-Maori and 53 per cent of Pacific applicants.

By mid-2016 the Governance Taskforce had consulted and endorsed ‘levers’ to help meet the goal including supporting all Māori new graduates into employment, building on current initiatives to promote nursing careers, and building Mâori faculty at universities and other providers.

The mid-year intake analysis indicate that the push may be paying off but the director of the Wānanga based kaupapa Māori nursing degree, Ngaira Harker, has expressed disappointment at the intial job offers for its first graduate cohort of 19 nurses who are part of the latest end-of-year ACE intake. At the end of November nine had jobs (just under half) which was a lower job rate than the 57 per cent of total applicants who had been offered jobs in the same time period, according to early ACE stats for this latest job match round.

Auckland biggest source of jobs

The cost of living in Auckland didn’t seem to put off new graduates seeking work for the three Auckland district health boards.

Auckland DHB had the highest number of applicants putting it as their first preference (118) and had 312 applicants in total expressing a preference for Auckland as their first, second or third preference. Waitemata DHB was the first, second or third preference of 229 applicants and Counties-Manukau had 200 applicants.

In all there were 260 applicants in the mid-year intake (just under 40 per cent of total applicants) who were graduates from the five nursing schools based in Auckland. The three Auckland DHBs between them took on 199 new graduates (Auckland DHB 87 and the other two 56 each) which was the equivalent of 44.5 per cent of the total jobs on offer nationwide.

The other two largest DHBs, Canterbury and Waikato – also got high interest with 108 graduates putting Waikato as their first preference and 106 putting Canterbury.

Canterbury DHB employed the highest number of new graduates in the country, 91, and Waikato employed 56.

*ACE Nursing mid-year job match round statistics

- 659 applicants took part in the ACE mid-year job match (461 were first time applicants, 169 second-time applicants and 29 were applying for their third round or more.)

- 389 jobs were initially offered by employers (338 NETP and 51 NESP)

- 327 applicants in July were electronically matched and a further 26 manually matched with jobs.

- 346 accepted the job offers (seven applicants failed state finals or declined job offers)

- 101 of the remaining 306 unmatched applicants were offered jobs before the ACE national talent pool closed on October 27.

- 447 (67.8%) of ACE applicants in total were successfully matched with a job.

- That left 190 (28.8%) of applicants still seeking a NETP or NESP placement as at October 27 and a further 22 (3.4%) of applicants had declined offers, failed state exams or withdrawn from the pool.

**The ACE Nursing Intake Summary Report was prepared by agency TAS (formerly known as DHB Shared Services) which owns ACE Nursing on behalf of the 20 DHBs.

NB: This article was corrected on December 22 to clarify that the report was released by TAS rather than the Ministry of Health.

]]>The just launched Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ child and adolescent asthma guidelines are designed to help nurses, doctors and other health professionals – delivering asthma care in the community to emergency departments – to provide simple, practical and evidence-based guidance for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in children and adolescents up to 15 years of age.

The new guidelines – developed by a team of health professionals under the guidance of Professor Innes Asher – include a shift from the ‘medical’ focus of the previous guidelines* to taking a holistic look at the ‘big picture’ factors that influence asthma outcomes.

Debbie Rickard, a child health nurse practitioner at Capital & Coast DHB who helped develop the guidelines, said the new guidelines were not just medical and encompassed many other factors for health professionals “such as how to support families to manage their child’s condition, and looking at the big picture of factors that contribute to child asthma, such as housing, environment and barriers to accessing services”.

A quick reference guide to the new Guidelines was published last week in the latest New Zealand Medical Journal (NZMJ), which said that the new guidelines were informed by recent New Zealand reports describing the growing impact of asthma – especially on children – and the inequities suffered by Māori, Pacific peoples and low-income families.

Lorraine Hetaraka-Stevens, the National Hauora Coalition nurse leader who was also part of the guidelines team, said underpinning the new guidelines was eliminating inequities. She said they included a focus on workforce, systems and broader determinants that impact on asthma, such as income and housing. The guidelines, she believed, also enabled consistent standards of care, which could the work of a wide range of health professionals working in a variety of settings; for example, school-based nurses and rural health professionals.

Dr Stuart Jones, Medical Director of the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ, agreed that addressing issues of social inequities is of paramount importance “if we are going to address the disparities in childhood respiratory illnesses and set all New Zealanders up with good lungs for life”.

“I think every child in New Zealand should have the right to be raised in a warm, dry, well-ventilated house, free of cigarette smoke and have good access to medical care,” said Jones.

David McNamara, respiratory paediatrician at Starship Children’s Health, said the guidelines were an important step in reducing disparities and improving outcomes for children with asthma and their whānau.

“The guidelines address the biggest challenges in asthma management: patient education, follow-up, motivation and improving adherence,” said McNamara. “By focusing on these we hope to lift the health and quality of life of children with asthma and reduce the burden of acute sickness and hospitalisation.”

Click here to download the full 33-page Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ child and adolescent asthma guidelines.

*The new guidelines are a complete update of the Paediatric Society of New Zealand’s Management of Asthma in Children aged 1–15 years, published back in 2005.

]]>The scholarships provide financial assistance – $10,000 for medical and dentistry students and $5000 for other health-related courses – to Pacific students who are committed to improving Pacific health. Applications are considered from both full-time and part-time workers (including district health board employees).

More information on the criteria and the online application form can be found here.

Applications close on February 6 2018.

]]>Iro, who has been a nurse and midwife in New Zealand, is currently the Cook Islands Secretary of Health and is the former Cook Islands Chief Nursing Officer and a former president of the Cook Islands Nurses Association.

Her appointment was announced this week in Brisbane by Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. It follows Dr Tedros pledging in May this year at the International Council of Nurses (ICN) Congress in Barcelona that he would reinstate a nursing role in his WHO headquarters team in Geneva.

Until recently also based in Geneva was former New Zealand chief nurse Dr Frances Hughes, who was chief executive of ICN from early 2016 until August this year. Also in Europe is New Zealand midwife Dr Sally Pairman who in January this year was appointed the chief executive of the International Confederation of Midwives.

On accepting the position, Iro said she was very honoured and humbled by the announcement.

“I think this appointment is going to be raising the profile of nursing and midwifery and I anticipate it will be encouraging and enabling for nurse to work to their full potential if countries are to achieve universal health coverage.”

Iro has more than 30 years’ experience in public health in the Cook Islands and New Zealand. For the first 25 years of her career she was a staff nurse, midwife and charge midwife at hospitals in the Cook Islands and New Zealand.

As president of the Cook Island Nurses Association in 2005, she helped to negotiate a salary increase for the country’s then-78 nurses after the nurses threatened a nationwide strike.

The nurse leader, who has master’s degrees in business administration and health science, went on to become the Chief Nursing Officer. In 2012 she became the first nurse to head the Cook Islands Ministry of Health when she became Secretary of Health.

As Secretary of Health she has implemented health reforms, including developing the country’s National Health Roadmap 2017-2036, the National Health Strategic Plan 2017-2021, and the Health Clinical Workforce Plan. In addition, she has helped to develop the Cook Islands Fellowship in General Practice, a postgraduate training fellowship for doctors working in the Cook Islands.

ICN president Annette Kennedy said ICN was “delighted” that Dr Tedros was true to his word and had reinstated the chief nurse role at WHO (after a seven-year gap). “ICN has met with Dr Tedros several times in the past few months to lobby for this position. He clearly recognises the value of nurses and has followed through on his promises.”

“I am thrilled to welcome Ms Iro to our team as WHO’s Chief Nursing Officer,” said Dr Tedros. “Nurses play a critical role not only in delivering healthcare to millions around the world, but also in transforming health policies, promoting health in communities, and supporting patients and families. Nurses are central to achieving universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. Ms Iro will keep that perspective front and centre at WHO.”

Kennedy said that ICN would continue to work closely with WHO to ensure that nurses had a chair at the policy-making table. “ICN looks forward to working closely with the WHO Chief Nurse and Director-General to support their work and represent the global nursing voice,” she said.

Iro’s appointment is the latest addition to the senior leadership team Dr Tedros announced last week, which includes representatives from every WHO region and is 60% women. It came at the 68th session of the WHO Regional Committee for the Western Pacific, which took place from 9 to 13 October 2017 in Brisbane.

Elizabeth Iro is married with three children.

*The article was revised on October 10 2017.

]]>

The pair were presented with their awards at the NZNO’s annual conference dinner this week.

Snell was the country’s first nurse practitioner in diabetes and was also the first NP to gain her PhD. She lead the project to develop the National Diabetes Nursing Knowledge and Skills Framework 2009, the diabetes nurse specialist prescribing pilot project for the New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes (NZSSD), and was also project leader for developing NZSSD’s online e-learning diabetes resource for primary care nurses.

NZNO president Grant Brookes presented the awards and said Snell’s contribution to nursing knowledge in diabetes was “very significant” and she was a crucial lead for the Health Workforce New Zealand diabetes workforce review.

He said Pepe Sinclair had worked for many years as a mental health nurse and had been involved in national and international research on mental health, wellbeing and nursing workloads.

“She is lecturer and a passionate advocate for better health outcomes for Pacific people,” said Brookes. He said the award went to a nurse who was a mother, grandmother and great-grandmother born in Rakahanga in the Cook Islands.

]]>

The Healthier Lives National Science Challenge, the Ministry of Health and the Health Research Council of New Zealand (HRC) joined forces to establish the $7.9 million research funding pool to tackle long-term chronic health conditions.

Yesterday’s $2.3 million announcement follows the $5.7 million announced for diabetes research in February.

Massey University research fellow Dr Riz Firestone, who is of Samoan descent, received almost $1 million in health research funding to develop and put into practice a Pacifika community-based intervention programme to reduce prediabetes, the precursor to full-blown diabetes.

Dr Michael Epton, Director of the Canterbury Respiratory Research Group at Christchurch Hospital, has received just over $1 million for a 24-month study that will address New Zealand’s low referral and attendance rates for rehabilitation programmes for people with multiple long-term conditions (LTCs), such as diabetes, heart failure, arthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Dr Firestone’s study will establish a Pasifika prediabetes youth empowerment programme involving Pacific youth (15–24 years old) from community groups in South Waikato and Auckland. It will build on Firestone’s recent HRC-funded pilot study in which a group of Pacific youth was taught how to plan and champion community-based interventions to counteract the key public health issues of obesity.

Epson says current approaches to rehabilitation for people with multiple LTCs focus too much on the biological aspects of their diseases and don’t include all the aspects of wellbeing that are important for improving health.

“Rather than developing new disease-specific interventions, we’ll work together with communities to develop and try initiatives that help people with multiple LTCs access community support, increase their sense of connectedness within their community, improve physical activity, and thus live lives they feel are fulfilling and worthwhile,” he said.

]]>

Particularly when we already have one that is set by the requirements of Nursing Council, i.e. scopes of practice, competencies and areas of practice for undergraduates. What we have currently gives us opportunities to develop programmes that are able to respond to the health workforce inequities for Pacific and Māori.

I come from a history of working in both a Bachelor of Nursing (BN) programme and developing and working in the Bachelor of Nursing Pacific (BNP) programme.

I have spent the last 13 years going over the same rhetorical questions around what makes our programme BNP and Māori programmes different.

Three areas for consideration are the notions of: what counts as knowledge, who gets to define what counts as nursing knowledge and who gets to decide what is appropriate for nursing curricula. In the past most who have had the opportunity to develop curricula are those who hold the hegemonic power.

I suggest that we don’t have a national curriculum in which one-size-fits-all, but that all graduate profiles include key specific outcomes, that we cover and the rest are specific to our unique programmes and communities we serve.

We have ‘been there and done that’ with a one-size fits-all approach and the experiment didn’t work for particular population groups.

This is too prescriptive, kills creativity and is detrimental to the diverse and complex requirements of the populations we serve. I’m open to discussion on what we need to improve on in relation to what Nursing Council already offers.

What I am not open to is becoming invisible in the debate on what counts as knowledge and whose knowledge counts in developing nursing curricula.

Furthermore I am not interested in contributing to the continuing invisibility and marginalisation of students and their access to nursing programmes.

National curricula are promoted by those who wish to maintain and increase power of control. These points of view are promoted by those who would see the increasing bureaucratisation of nursing rather than developing a nursing workforce fit for purpose from a health consumer’s, families’ or communities’ perspective.

]]>The study is based on the 15,822 respondents to the 2014-15 New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study which asked people about their satisfaction with health care access and also included questions about their personality traits, location and socio-economic situation

Overall the University of Auckland study, published in the New Zealand Medical Journal today, found that the majority of participants (68.4%) were highly satisfied with their access to health care, 25.3 per cent were moderately satisfied and 6.1 per cent had low satisfaction

But when this was broken down by ethnicity it was found that nearly 72 per cent of European/ Pākehā respondents were highly satisfied compared to 61 per cent for Māori, 62 per cent for Asian and 63 per cent for Pacific.

The study did find various psychological factors or personality traits were linked to higher satisfaction with people scoring higher on extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and honesty expressing greater satisfaction. And people scoring high on neuroticism (anxiety and insecurity are example traits) or on ‘openness to experience’ (for example curiousity and imaginativeness) had expressed lower satisfaction levels.

But when it controlled for demographic and psychological factors it found that that Māori, Asian and Pacific were still found to express lower satisfaction with their healthcare access than European/ Pākehā.

“This result can be linked to findings that ethnic minorities are more inclined to experience language, information and cultural barriers to healthcare, and the lack of cultural competence among medical professionals,” said the researchers.

“Our findings further suggest that perceptions of low healthcare access among ethnic minorities cannot be fully explained by population differences in socio-economic or personality factors.” They believed that to increase healthcare access for ethnic minorities, it was essential to develop tailored health interventions targeting the unique cultural barriers faced by Māori, Asian and Pacific people.

The study did find that similar to previous studies that people with lower incomes or lower socio-economic status and higher deprivation exhibited decreased satisfaction with their healthcare access.

It also found that people report higher self-rated health expressed great satisfaction – along with people who had a partner, lived in an urban area or had no children.

Study: Demographic and psychological correlates of satisfaction with healthcare access in New Zealand by Carol HJ Lee and Chris Sibley, New Zealand Medical Journal, Vol 130, 1459

]]>Her research was prompted by her own nursing work and questioning whether patients understood the information they were provided following a cardiovascular risk assessment.

“I found a lot of people would get a CVD risk assessment done, but not know why they were there or what the results meant.

“The disease is known as the ‘silent killer’ because patients might not know they are at risk. They feel fine, they feel strong, and if they aren’t fully informed, they may not think it’s necessary to make lifestyle changes.”

She interviewed 16 Samoan patients and seven practice nurses in the Wellington region and found poor comprehension of English and low health literacy created barriers to many Samoan patients’ understanding of CVD, which resulted in a low uptake of management strategies such as exercise, a healthy diet and regular risk assessments.

Taueetia-Su’a also found that cultural differences impeded Samoan patient’s understanding and adoption of lifestyle changes.

Her thesis highlighted the importance of the nurse’s role in primary health services and amongst her recommendations to practice nurses was ensuring good communication to enhance partnerships between Samoan people and health professionals including offering culturally appropriate service that embraces fa’a Samoa—the Samoan way of doing things— and the community.

“Samoan culture is very much centred on the family, community and village, not the individual. If the health system is to effectively motivate the patients to lower their CVD risk by eating healthy and exercising, it needs to involve the whole family. Family members should be invited to attend risk assessments to hear from the doctor or nurse because it’s likely the mum is doing the cooking and the family can support lifestyle changes.”

She says letters sent out to patients asking them to come in for a CVD risk assessment should be clear and unambigious, appointments should allow time for questions and, when appropriate, use community health workers and family to assist in explaining risks and lifestyle changes. An easy and practical health education plan should be developed and followed-up to help support lifestyle changes like physical activity, diet and the regular taking of medication.

Health Services Research Centre director Professor Jackie Cumming says Taueetia-Su’a’s research identifies some key issues that health services need to take into account to work better for Samoan people in relation to CVD.

]]>The Church is looking for someone just like you to…

An elderly Samoan man has just turned up, can you translate…

Auntie is sick, can you just pop round after work…

We are looking for a Māori nurse for this working party, you’d be great…

Sorry to wake you up, but Mrs Toleafoa from down the street has had a turn…

Few nurses see their profession as just a job. But the expectations placed on Māori and Pacific nurses by themselves, their employers and their communities can make an already demanding profession even more challenging.

This is particularly true now, when health strategies stress the need for more Māori and Pacific nurses to help counter poor Māori and Pacific health statistics, while the percentage of Māori and Pacific nurses still lags far behind the actual populations (see statistics sidebar).

So there are too few nurses and too much need. How does this impact on Māori and Pacific nurses? And how do they cope?For her PhD thesis, organisational psychologist Dr Lisa Stewart looked at whether the occupational stress experienced by Māori health workers was different from their mainstream counterparts.

She says two themes emerged, one being the cultural expectation from Māori communities – shared by Pacific communities – that Māori nurses and other health workers give back to the community in some kind of service. The second was institutional racism – often caused by misunderstandings and a lack of cultural competence – which added to Māori health workers’ stress loads.

Community expectations

Māori and Pacific are not the only cultural groups where community and family expectations outside of work are important, says Stewart. But that cultural expectation is very real.

She recalls as a young university student in the 1980s being told by Māori student association leaders that, on graduating, Māori students like herself should help their whānau, hapū and iwi in some way, be it serving on the marae committee or helping out at kohanga reo.

Kerri Nuku, kaiwhakahaere of Te Rūnanga o Aotearoa NZNO, agrees and says being a nurse within a whānau group can lead to additional expectations.

“You will be the contact person for aunty down the road who is not really sure whether she should rock on down to the doctor’s or just put a bandage on it,” says Nuku. “We hear stories of nurses, particularly who work in rural communities with high population Māori, that in the supermarket people come up to you when you are trying to do your shopping at the weekend and ask you for your advice because you are whānau, because you are Māori and because you are approachable.

“Then if you’ve got somebody sick within the whānau, you go to work, do your work and then come home and take over your shift caring for the sick whānau member. You build your own roster around them so that caring doesn’t stop when you leave the hospital grounds or workplace.”

This sense of duty begins as nursing students, believes Jackie McHaffie, who is in charge of the Tihei Mauri Ora stream of Wintec’s bachelor of nursing programme and has been involved with the programme for around 15 of its 25 years.

“There’s a cultural component that is always going to be there and will add to your duties above and beyond being a registered nurse.

They try and give as much as they can back and in doing so they often burn out.”

Dr Sione Vaka, Tonga’s first male nurse, who is now a lecturer for Massey University’s School of Nursing, says likewise there is an expectation from the Pacific community for nurses to deliver as much support as they can. For him this means that in addition to his day job he is on the executive of the Tongan Health Society; he’s also vice-president of the Pacific Island Mental Health Professional organisation, chair of his church’s health committee, a member of both the Tongan Nurses Association of New Zealand and the Aotearoa Tongan Health Workers Association, informal mentor to Pacific postgraduate students from a variety of institutions, feedback provider on Pacific mental health research – and he also holds various other community service positions. And this is all after cutting back his out-of-work commitments to fit his targeted areas of expertise.

Workplace expectations and institutional racism

Then there are the workplace expectations that can be placed on a scarce and already stretched thin Māori and Pacific nurse workforce.

Stewart says one of the stress issues unique to Māori that emerged as a theme during her research (which assessed the work stress levels of 130 Māori health workers, including nurses) was institutional racism; for example, workplaces playing lip service to the Treaty of Waitangi and related policies aimed at improving health outcomes for Māori.

And Stewart says when organisations do recognise bicultural responsibilities – like holding a powhiri to welcome new graduate nurses – non-Māori managers can see this as a Māori-only role, adding an extra layer to Māori nurses’ workloads.

She says it doesn’t have to be that way. A positive example was an organisation she worked at where it was clearly expected that a Māori staff member would lead the karanga but all ethnicities and nationalities were invited to be part of the waiata group that performed support songs and helped set up the powhiri, including food if that was involved.

McHaffie adds that Māori nurses who work for organisations where they may be one of the few or only Māori can find themselves approached for advice on all things Māori, as well as being expected to say the karakia or sing a waiata. But there are also high cultural expectations placed on Māori who are working for Māori providers, which can extend the working day and week for Māori if they need to attend hui or practice for iwi cultural events. Then on top can come expectations for postgraduate study. McHaffie says that over the years she has seen some graduates burn out after struggling to cope with the pressure to be not only a good nurse but also a good Māori nurse.

Nuku says she’s also heard of hospitals placing Māori new graduates in particular units or wards well known to be “not conducive to Māori … oh I will just put it out there… they are areas known to be racist” in the hope of trying to change the behaviour of the staff. “So these are conscious decisions that are being made that put our nurses in unsafe places because nobody has dealt with the issue of racism.”

Nuku and her NZNO colleague Eseta Finau, who heads the Pacific Nursing Section (PNS), also both receive reports of interview processes and panels that are seen as discriminatory and demoralising for Māori and Pacific nurses.

Finau says an ongoing issue for many Pacific-trained registered nurses is being used as “cheap labour” by rest homes while struggling to afford time off to attend the English language training they need to become registered in New Zealand.

Another workplace expectation often adding to the stress loads of already stretched nurses is the belief that Māori and Pacific nurses should be allocated the Māori and Pacific patients, without the workload impact being considered.

“Why are Māori patients the sole domain of Māori nurses and why are Tongan patients the sole domain of Tongan nurses? Aren’t all patients the domain of all nurses?” asks Stewart.

Vaka echoes this, saying sometimes non-Pacific nurses are keen to transfer the care of a Pacific patient to a Pacific nurse, saying they would do a better job.

He believes it is important to encourage other nurses to be comfortable and confident in working with Pacific people, rather than trying to refer all patients to a potentially already overloaded Pacific nurse or Pacific health service.

Not a burden

Community, and employer, expectations may be high of Māori and Pacific nurses but often so are the nurses’ expectations of themselves in doing their best to improve the health outcomes of their people.

Stewart says Māori and Pacific nurses don’t usually see this work as a burden but more a natural extension of being part of a community. “I find when I’m giving back to a really good cause – and I’m helping the whānau in some way – as much as that’s work, it also feels really, really good and has a way of energising you too.”

So giving can be good – it’s over-giving that can be the issue.

Finau says family upbringing is also a major influence, with multitasking just something you do when you’re from the Pacific. “Because at home you grow up with so many kids around, there are family things and church things … and you just learn to juggle and cope with things. Giving back to the community is just another thing you take on and being a nurse you manage your time.”

Stewart’s research found that occupational stress was not lower in kaupapa Māori health providers than in mainstream providers – on the contrary, role overload and organisational constraints were all higher. But the coping strategies were better, which matched earlier research findings (see retention sidebar) that the top factors encouraging Māori health workers to stay with a health provider included being able to make a difference to Māori health and to their iwi or hapū, and that Māori practice models and approaches were valued.

Nuku agrees, saying Te Rūnanga o Aotearoa used to see nurses shifting from Māori provider groups to DHBs because of the money, but, despite pay parity being an ongoing issue (see sidebar), she says the reverse is also happening. “What we are feeling is that there is a trend that they are going back because they can’t cope with the amount of racism that is happening in workplaces.” There is also a frustration that poor Māori health statistics are used as “a patu [weapon] against ourselves”; innovative strategies that do work don’t get sustainable funding; and the Māori nursing workforce is still static, despite strategies aimed at boosting recruitment and retention.

“I don’t think we have looked enough at how we support Māori and Pacific nurses in the workplace,” she says.

Cultural competence of all staff important

One step in the right direction, believe many, is placing value on cultural, as well as clinical, competence in the workplace.

“If all of our nurses were culturally competent to deal with all of the cultural groups that they see in their practice, then the burden of being responsible for Māori patients becomes everybody’s responsibility – not just Māori nurses’ – and Tongan patients are not only the responsibility of Tongan nurses,” says Stewart.

Vaka says he is aware, through non-Pacific nursing friends, that some have a fear they will do something wrong when caring for Pacific patients, so they look to transfer them when possible. He agrees a better approach is for all nurses to upskill themselves culturally, seek advice and “have a crack” themselves in looking after Pacific people.

“If we are able to learn more about one another and how to work with different cultures – it is such a diverse community that we are living in at the moment – it would be improving our overall health care as well,” he says.

Stewart also believes the handover of patients to Māori or Pacific nurses is not intentionally malicious but more a lack of understanding and a lack of confidence in being able to work effectively with those client groups. “The reality is that as a Māori when I go into a health service would I prefer to work with a Māori member of staff? Sometimes I would, but I know the reality is that I won’t. But what I do expect as a Māori health user is that when I use the health services I get treated with dignity and respect in the same way that every other cultural group would expect to be.”

Nuku says there are expectations that registered nurses be culturally competent and clinically competent “but time and time again clinical competency outweighs the need for nurses to be seen to be culturally appropriate.” She says, as an example, that nurses must undergo ongoing professional development to be deemed clinically competent, whereas it is accepted that nurses will be still culturally competent after attending, though not necessarily participating in, a Treaty of Waitangi workshop five years previously. “It’s almost like a default that we sanction ignorance around working in Aotearoa and the unique relationship we have as tangata whenua.”

Mentoring and supervision

Having strong support mechanisms for Māori and Pacific nurses in hospitals and other organisations is also seen as key to recruiting and retaining nurses.

Nuku says strong mentoring programmes are needed not only for new graduates but also for Māori nurses throughout the continuum of nursing until retirement.

McHaffie also recommends that her graduates find a cultural advisor or mentor from whom they can obtain advice or talk to about situations that may arise. Nurses can also seek support from the Māori health units that are often within larger DHBs.

What is needed and wanted by many Māori nurses, believes Stewart, is cultural supervision, just as clinical supervision is offered to nurses in the mental health sector, to support best practice.

Networking with other Māori health professionals also emerged as an important coping strategy for stress, says Stewart,

but this was often seen by non-Māori managers as a social activity, rather than a chance to share ideas, download and support each other. “There seems to be a lack of understanding about what organisational conditions need to exist in order for Māori nurses and other health professionals to be most effective at their job.”

Likewise, Pacific Nursing head Eseta Finau says one of the most important roles of the country’s various Pacific nurses associations – such as the umbrella NZNO Pacific Nursing Section, the Samoan Nurses Association, the Tongan Nurses Association (which she also leads), and other Pacific nursing groups – is the support and mentoring they provide for members.

But when she invites nurses to join the NZNO Pacific Nursing Section and help to train a new generation of leaders, she says employers often won’t allow them to attend in work time. “Yet this is all towards the wellbeing and the future of our Pacific people in the communities that we live in.” With many Pacific nurses being the breadwinners for their family, it is a big ask to take a day off to attend a meeting, but committed nurses will use precious annual leave to attend, which Finau says is “just not fair”.

She says one way to deal with stress and burnout is by supporting people to be trained to fill leadership positions such as in the PNS to share the load.

Learning when to say ‘no’

An important skill for preventing burnout is the art of when to say ‘no’. Culturally, this is not always simple for Māori and Pacific nurses.

Stewart says it is actually harder for Māori and Pacific nurses to say ‘no’ to their cultural communities then it is to say ‘no’ to people at work.

Finau acknowledges saying ‘no’ can be an issue for Pacific nurses. “Some of us are just too polite and say ‘yeah’, ‘yeah’, ‘yeah’ and don’t say ‘no’ to anything. And commit and commit and you can tell they are over their limits. It’s a cultural thing – just trying to be nice and serve others rather than thinking about what you can do and what you can cope with.”

The result is that nurses can learn to cope and over-cope, but Finau says she can say ‘no’. “I know when to say ‘no’ and tell them when this is enough and when things are rubbish.”

Vaka says he used to overcommit to a lot of community projects and, combined with his PhD study, this left too little space for family time. “No wonder my wife would call my PhD the ‘other woman’,” laughs Vaka. He realised he had to be very selective in what extra commitments he said ‘yes’ to and now, unless he believes his expertise in health and research is going to be well-used, he will recommend another person. But it is still not easy.

“At the moment I am still struggling to say ‘no’ to people. But I think I know now how to say ‘no’ nicely,” laughs Vaka. “And I think for us Pacific people we need to know when to say ‘no’, as we need to reassess when we have enough on our plate already if we want to deliver a good quality service [to our work and our community]. Don’t be scared of saying ‘no’.”

Stewart agrees that it helps if nurses prioritise which goals are most important to them and decide how to make the best use of their time and expertise to meet those goals. This includes being aware of their own capabilities and when they are at risk of burnout “rather than just blindly saying ‘yes’ to everything.”

Conclusion

With its small numbers of nurses and high population needs, the Māori and Pacific health workforce is unfortunately at real and ongoing risk of burnout. Helping the existing workforce look after itself seems essential if that workforce is to have the rapid growth required to meet government targets and community needs.

One part of the equation is for funders and employers to keep working at better supporting and fostering this scant workforce. Another may be for communities to be realistic in the expectations they place on their nursing members. The last is for nurses themselves to do their best to look after themselves (see sidebar for some ideas).

“Nurses are no strangers to reflective practice – it is just a matter of reflecting on themselves rather than their work,” says Stewart.

“The reality is that if we aren’t looking after ourselves, how can we do our best to look after our communities? The best way we can serve our communities is to make sure we are well ourselves.”

Pacific nursing students: walking the talk

Loma-Linda Tasi got tired of teaching nursing students about Pacific people’s negative health statistics.

The nursing lecturer, co-ordinator for year two of Whitireia Community Polytechnic’s Bachelor of Nursing (Pacific), decided she had to start somewhere to make a difference and a good place to begin was with herself and her students.

Her philosophy is to try and build a healthy lifestyle into everyday living to stop the real risk nurses face of being so busy looking after others that they forget to look after themselves.

So her personal journey has included giving up her car so she walks to work most days, her teenage kids are more active and the temptation is removed to drive to get takeaways after a busy day.

Her teaching journey includes supporting her very committed students to build an understanding of other’s health needs by turning it around and looking at their own health needs first.

“The statistics tell us that Pacific people are highly represented in rates of obesity and chronic disease and you can bet that that statistic is represented in the classroom too.” The pressures of study can also impact negatively on health with students working long hours and filling up on cheap hot chips from the student café.

Empowering students

Tasi says she tries to takes an empowering holistic approach so sets aside time in the study week for students to gather in small groups to set a simple personal health goal for the year; examine the evidence behind it, identify the challenges (including being time and money poor students) and support each other through the year to meet that goal; be it quitting smoking or eating more healthily.

She backs this in the classroom by teaching the science behind healthy lifestyle changes that can reduce the risk of chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease.

For example when she does a session on acids, alkalis and blood pH she makes students record all they ate in the previous three days. They arrive in the classroom to find acidic written up on one side of the white board and alkali on the other and she gets them to write-down each serving of vegetables, chips, fruit, pie, alcohol, soft drink or cereal they ate or drank on a Post-it note and stick them on the appropriate side of the board.

She says there is a lot of laughter during the exercise but quickly the acidic side of the board fills up giving students a graphic depiction and reality check that their diet is not okay. “Over the term students report back that they’ve changed a lot in their family’s diet and also saved money in some cases.”

Tasi’s aim is to empower Pacific people to reverse unhealthy lifestyle patterns, caused by shifting to New Zealand, as part of a nursing curriculum that emphasises Pacific nurses understanding who they are, where they came from and equipping them with the knowledge to rebuild a healthy lifestyle one step at time; starting with their own family, their friends and, in time, the community they care for as nurses.

Advice on stress management

- Learn to recognise and notice your own symptoms of stress

- Find out what resources are available either within or outside your organisation to prevent, reduce or manage that stress.

Try:- workplace exercise or mindfulness classes

- EAP (employee assistance programmes) that may offer counselling

- Look to culturally relevant models of health as a framework for managing your stress: i.e. Professor Mason Durie’s Māori health assessment framework, known as Te Whare Tapa Whā (1982) and the Pacific health and wellbeing model Fonofale (2009), developed by Fuimaono Karl Pulotu-Endemann.

Both of these models have four elements in common:- Physical health: could be pilates, netball, jogging, touch rugby, dancing, healthy eating, etc.

- Mental health: mindfulness or meditation or time out to simply read or go for a quiet walk.

- Spiritual health: could be church or prayer or taking part in cultural activities such as kapahaka and cultural festivals.

- Social health: connecting with your whānau/family and with other communities you are part of (be it your church or your touch rugby team) to help nurture and re-energise you.

- Remember that giving is good, but over-giving is not good and can impact on your own health, which is not good for the community you serve.

- Be aware of your limitations.

- Set priorities for what goals you value most and be strategic in how you allocate your time and expertise to best support those goals.

- Learn when and how to say ‘no’ in a way you are comfortable with.

- See related articles in this edition on general stress management, being work-fit and looking after yourself.

Barriers and enhancers sidebar table

Barriers to retention of Māori in the health and disability sector* |

|

| In mainstream roles, expected to be expert in and deal with Māori matters | 65% |

| Māori cultural competencies are not valued | 64% |

| Dual responsibilities to employer and Māori communities | 58% |

| Lack of or low levels of Māori cultural competence of colleagues | 58% |

| Limited or no access to Māori cultural competency training | 51% |

| Limited or no access to Māori cultural support/supervision | 48% |

| Racism and/or discrimination in the workplace | 39% |

| Isolation from other Māori colleagues | 33% |

Retention enhancers for Māori in the health and disability sector |

|

| Making a difference to Māori health | 92% |

| Making a difference for my iwi/hapū | 89% |

| Being a role model for Māori | 80% |

| Ability to network with other Māori in the profession | 83% |

| Strengthening Māori presence in the health sector | 92% |

| Being able to work with Māori people | 89% |

| Māori practice models and approaches valued | 81% |

| Opportunities to work in Māori settings | 80% |

| Source: Participants’ ratings of importance of barriers as either ‘quite a lot’ or ‘major importance’ in research carried out for RATIMA et al. (2007), Rauringa Raupa, Ministry of Health. (Republished in Lisa Stewart’s ‘Māori Occupational Stress’ thesis.) |

Stats

Māori

As at 31 March last year, 3,510 practising nurses – comprising 15 nurse practitioners, 3,245 registered nurses and 250 enrolled nurses – identified as Māori. This represents seven per cent of the total nursing workforce.

In the 2013 census, Māori comprised 15.6 per cent of the total New Zealand population and were younger overall than the non-Māori population (a third were aged under 15).

Pacific

There are more than 40 different Pacific ethnic groups in New Zealand, each with its own culture, language and history.

As at 31 March last year, 1,733 practising nurses – comprising three nurse practitioners, 1,628 registered nurses and 102 enrolled nurses – identified with at least one Pacific ethnic group. This represents three per cent of the total nursing workforce.

In the 2013 census, people identifying as Pacific comprised 7.4 per cent of the total New Zealand population and were also younger, on average, than the total population, with more than a third of Pacific people aged under 15 (compared with

z20 per cent of the total population).

Twenty-five per cent of Pacific nurses (425) were trained overseas – the majority in a Pacific nation.

Health Statistics

Ministry of Health statistics show that Māori have higher rates than non-Māori for many health conditions and chronic diseases, including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, arthritis and asthma. About two out of five (40 per cent) Māori are obese, compared with around a third (33 per cent) of the total population.

Ministry of Health statistics show Pacific people have a higher burden of chronic disease, such as diabetes, ischaemic heart disease and stroke. Two out of three Pacific adults are obese, compared with a third of the total population and the diagnosis rate for diabetes is approximately three times the rate for the total population.

Socioeconomic determinants of health (such as unemployment, income, education and housing), plus lifestyle behaviours and cultural, historical and other factors all impact on the health risks and unmet health needs of Māori and Pacific people.

Enough is enough

Pay equity wanted for Māori and iwi health provider nurses

Back in 1908, one of the country’s first Māori registered nurses and midwives, Akenehi Hei*, struggled to get the government to pay for her work. (See her story below.)

More than a century later, nurses working for Māori and iwi health providers are still struggling with pay equity issues, says Kerri Nuku, kaiwhakahaere of Te Rūnanga o Aotearoa NZNO. Nuku says the pay gap between iwi nurses and their district health board counterparts has now got to the point that she knows of iwi nurses taking on extra jobs or contracts to make up for the low wages and to ensure a reasonable standard of living for their families.

The journey for pay equity for these nurses began back in 2006. It followed the ‘pay jolt’ ratified in 2005 for district health board nurses, which initially saw the pay gap widen between all non-DHB nurses and their DHB colleagues. A further pay gap subsequently emerged between nurses employed by Māori-led healthcare organisations and their counterparts employed by primary health organisation (PHO) funded general practices. At the crux of the issue is a government funding model for Māori and iwi health providers that differs from that of a typical neighbourhood general practice.

An 11,000-plus petition was presented to Parliament back in July 2008, pointing out the inequity and calling for the Government to work with NZNO and Māori and iwi PHC employers so that pay equity could be funded and delivered to their nurses and other health professionals.

In 2009, in response to the petition and other evidence presented, the Health Select Committee recommended to Parliament that a working group look further into the petition issues – including recruitment and retention issues for the providers that deliver targeted services to Māori communities – and report back in six months. But Nuku says the Committee’s recommendation was vetoed by the Government and the working group never formed.

She says there is also increasing frustration that health workforce projects keep setting Māori health workforce targets to meet health needs but as yet New Zealand still doesn’t have a single data repository showing what the current Māori workforce looks like, let alone addressing pay equity issues impacting on retention and recruitment of that workforce.

Nuku says after a decade of unsuccessfully petitioning, lobbying and negotiating for more data and improved funding so Māori and iwi health providers can close the ever-widening pay gap, the rūnanga have said “enough is enough”.

“How do we shine the spotlight on this discriminatory practice that has been going on for way too long?”

There are documents such as 2012’s Thriving as Māori 2030, which says health services need to “at least triple” the Māori workforce by 2030 to reflect the communities they serve, and the tripartite Nursing Workforce Programme, which late last year set 2028 as the date that the percentage of Māori nurses needs to match the percentage of Māori in the population. But Nuku says that initiatives to date have done little to grow the Māori proportion of the nursing workforce, which has been basically static since the 1990s.

“So we have been feeling quite aggrieved for a wee while,” she says. But after years of being wary of speaking out, she says rūnanga members are readying themselves for a ‘big year’ in 2016 and to start challenging the status quo. She says they are now viewing pay parity for Māori and iwi providers, and the lack of information on Māori health workforce data, as human rights issues. To this end, NZNO has written to the Universal Periodic Review (the United Nation’s Human Rights Council process that reviews the human rights situations of all 193 UN member states) to express its concerns about the issues and has also raised its concerns with New Zealand’s Equal Employment Opportunities (EEO) Commissioner, Dr Jackie Blue.

Pioneering nurse Akenehi Hei

In 1901 Akenehi Hei began a basic nursing skills programme intended to make her an “efficient preacher of the gospel of health” when she returned to her village as a “good, useful wife and mother”. In 1905 the scheme was extended to offer full nurse training and the still-unmarried Hei qualified as a registered nurse in mid-1908. She quickly completed her midwifery training in the same year in readiness to be part of a 1907 Public Health Department scheme to employ Māori district nurses (working in public hospitals was not envisaged or encouraged for the first Māori nurses.)

But by 1908 there were still no government funds allocated to pay for Māori district nurses and it wasn’t until June 1909 that she was offered a two-month post nursing in a Northland typhoid epidemic. After that it took several more months until she was finally offered another post in New Plymouth. Tragically, she succumbed to typhoid herself in late 1910 after returning to Gisborne to nurse family members ill with typhoid.

Her biography in Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand states she not only had to deal with institutional racism – her postings were seen as a test case “to see how these Māori nurses act” – but also with little support from a department which was concerned with minimising costs and was not fully committed to Māori health work.