Fundamental cares provide the foundation for all nursing care. So, what are fundamental, ‘basic’ or essential cares, and what enables or stops nurses providing this care?

By Claire Minton and Lesley Batten

Reading the article Fundamental nursing care: getting back to ‘basics’ and undertaking this learning activity is equivalent to 60 minutes of professional development.

This learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council registered nurse competencies: 1.1,1.5, 2.4, 2.6, 2.8, 2.9, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 4.3.

Learning outcomes

Reading and reflection on this article will enable you to:

- define the Fundamentals of Care Framework and its importance to clinical practice

- describe the importance of the nurse-patient relationship within the framework

- explore how the framework can inform your practice

- consider healthcare system barriers and facilitators to the provision of fundamental cares.

A video to start you thinking

Before you start reading this article we recommend you watch the short video (link below) and reflect on how nurses in all settings may learn from this woman’s experience: https://heartsinhealthcare.com/every-intensive-care-nurse-doctor-watch-4-minute-film-will-change-forever/

Nursing is under increased scrutiny to deliver care that follows the principles of patient-centredness, with the aim of improving patients’ experiences and outcomes.

In patient-centred care, whānau or family and the patient are partners in care delivery. Care labelled as ‘fundamental’ is now identified as essential to reduce harm, optimise recovery, for positive patient experiences1 and to be congruent with the delivery of patient-centred care.

However, there is increasing concern in the international literature that these cares are often omitted1. The reasons for these omissions are complex but the most common are nursing shortages, organisational cultures, and a mechanistic and task-focused care approach2.

The World Health Organisation global strategy for health care is ‘people-centred’ not ‘disease-centred’3, and fundamental cares provide the foundation for all nursing care. So, what are fundamental cares, and what enables or stops nurses providing this care?

The ‘basics’ are not basic

Some call fundamental cares ‘basic nursing care’, but this implies care that requires less skill. This argument then supports the delegation of ‘tasks’ to unregulated workers, like the emergency department volunteer providing food and drink to patients: This is ‘basic care’ if the patient is otherwise fit and well, but for the frail elderly patient who hasn’t had anything to eat or drink in 24 hours, food and fluids are no longer ‘basic’. Its provision, in a safe, appropriate, and monitored manner is essential. ‘Essential care’ is another label, which does acknowledge the pivotal place of this care. The degree of complexity in health care today, with an aging population, increasing numbers of patients with multi-morbidities, and more use of technology and pharmacology, results in the need for high-quality fundamental care across the healthcare continuum1 to address these complex needs.

However, the lack of an agreed definition on what constitutes fundamental care, and the nature of patient and family or person-centred care, has created a challenge in the reprioritisation4 of care needs.

Many policies, standards and interventions are designed to improve all nursing care, based on the recognition that there are widespread failures in the delivery of fundamental cares – across the globe. Providing fundamental cares as part of patient-centred care requires sensitivity to patients’ (and families’) unique physical, psychosocial, cultural and emotional needs, and therefore nurses require the knowledge, skills and models of nursing care that are congruent with these approaches. Healthcare organisations also need to support nurses working in ways that recognise this approach to care.

As nursing knowledge has advanced, nursing theories have developed and emphasised a more holistic perspective, where the person has primacy in all aspects of care. This can be seen in theories such as Jean Watson’s theory of human caring, which focuses on the art and science of human caring, and offers a way of conceptualising and maximising human-to-human interaction in nursing practice. Furthermore, Katherine Kolcaba in 2003, returned to the nursing theory origins of Florence Nightingale, with her ‘Comfort Theory’ recognising that increasing technological advances can be detrimental to a patient’s comfort2. The Fundamentals of Care Framework (the framework) was developed to capture the complexity of everyday practice by describing the practical aspects of caring and nursing6.

Fundamentals of Care Framework

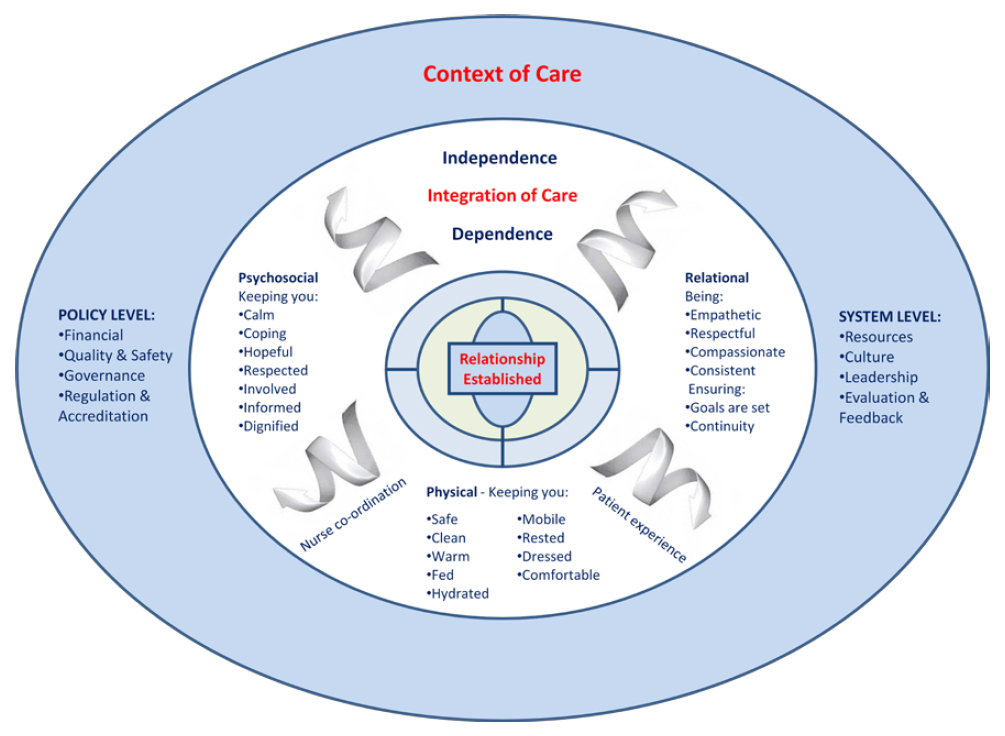

The Fundamentals of Care Framework articulates the key principles of care using the clinical and research expertise of members of the International Learning Collaborative (ILC), an organisation dedicated to transforming the delivery of fundamental care internationally through research and education. The framework has three dimensions:

- Establishing a relationship with the patient.

- Assessing.

- Delivering physical, psychosocial and relational care within the wider contexts of health care5.

All three dimensions are necessary to deliver quality fundamental care4. Within the framework, the relationship between the nurse and patient (and whānau or family) is central and therefore must be established first (see figure 1).

Figure 15.

Nurse-patient relationships

The nurse-patient relationship is integral to meet the needs and health outcomes of the patient, to ensure no harm, and that they are supported throughout their patient journey. A positive and trusting nurse-patient relationship is essential for the delivery of fundamental care within the framework7. The factors required for the establishment of the nurse-patient relationship are listed in box on right.

Once the nurse has established a trusting relationship with the patient (and whānau), they focus on how they can address the person’s fundamental care needs, which include psychosocial, physical and relational needs.

These considerations should occur concurrently in any care encounter. The framework focuses on the practical acts of helping patients manage their fundamental care needs, such as personal hygiene, sleep, rest, feeling safe, being respected and having a choice – which are essential to meet patients’ unique caring and safety needs. This requires nursing behaviours to encapsulate factors establishing and maintaining positive nurse-patient relationships, such as recognising patients as experts in their own experiences, finding out what is important to the patient, and showing insights into patients’ experiences.

The final dimension of the framework refers to the context of care. This dimension recognises a healthcare organisation has its own culture that can either hinder or enable care delivery; however, it also recognises the need for policies and resources that support the delivery of fundamental care8.

Reflection

- Reflect on your prior understanding of fundamental care. Does it differ from the Fundamentals of Care Framework?

- How does your organisation support you providing fundamental cares?

The patient-centred approach for improved outcomes

It is no surprise that patient-centred care focuses on the needs and priorities of the patient, and their whānau or family, to achieve positive outcomes and experiences.

When nurses establish positive relationships with patients, it helps them deliver care that is patient-centred, because it can support patients to make informed decisions, promotes their dignity and advocates their needs. The nurse-patient relationship is also central to the delivery of fundamental care as the nurse must connect meaningfully with patients to understand their care needs through compassion and respect6.

Patients participate in care as they are able within the framework. Closely aligned with this is the nurse-patient relationship. This relationship and ‘knowing the patient’ enables nurses to detect signs of deterioration, recognise changes in patients’ physiological and psychological parameters, and then initiate appropriate interventions8. Not knowing the patient, on the contrary, creates potential negative consequences for patients, including late or delayed detection of deterioration, and depersonalised care because patients can be objectified9.

Missed fundamental cares are also associated with numerous other harms like pressure injuries, increased infection rates and emotional distress from loss of dignity, autonomy, and lack of compassionate care10.

Barriers and enablers to delivering fundamental cares

The ILC group list many barriers and enablers to the delivery of fundamental cares.

The core barrier is that care identified as fundamental is invisible across the healthcare system, including in education, practice, research and policy.

Consider how you document, for example, developing a relationship with the patient and their whānau or family. How do you know what is important to them, to their wellbeing and to help them with their recovery goals?

Is this sort of information valued and visible in your clinical setting? Other barriers include medical dominance and the healthcare system structures.

Medical dominance

Dominance of the medical model creates a potent barrier to the provision of fundamental cares in many practice settings. Consider how often you see the following in your practice setting:

- The biomedical model prioritises interventions for diagnosis and cure first.

- The biomedical model devalues fundamental care as less important to illness and recovery.

- Physical problems, needs and care (e.g. nutrition, mobility, hygiene) are prioritised over social, psychological, relational, cultural and spiritual determinants of health.

- Relationships formed with compassion and empathy are thought to add little to cure.

- Physical tasks are assigned to different allied healthcare professionals, and to non-regulated workers, without a comprehensive care planning approach.

When using the Fundamentals of Care Framework the nurse acknowledges the causes and consequences of illness at multiple levels, including recognising the biological, psychological, cultural and social aspects of illness. The framework, when applied holistically, changes the focus of nurses’ work, which is underpinning other important diagnosis and disease focused work.

Healthcare system

The healthcare system provides both barriers and enablers to the provision of fundamental cares:

- Nursing work can be conceptualised as technical and physical work, at the expense of relational components.

- In an attempt to reduce paperwork, assessment forms and care plans with tick boxes can result in reduced consideration of the person’s needs as a whole and how these interventions come together to create an integrated care plan.

- The metric approach to patient outcomes relates to risk, and not positive patient experiences – both are needed.

- Only physical fundamental cares are visible – the psychological and relational aspects are often poorly documented, therefore invisible and unmeasurable.

- Task-based capacity demand systems can result in nurses becoming disengaged from patients and devaluing fundamental cares, used for falls and pressure injury planning.

- Caring is not always rewarded or recognised, resulting in some nurses devaluing it or becoming morally distressed when they cannot deliver care they identify as essential.

- Care ‘rationing’ and time pressures mean nurses prioritise tasks, with some fundamental cares left undone.

Nursing devaluing fundamental cares

There are also components within the structure of nursing that create barriers:

- Highly specialised and technical care is seen as more prestigious.

- Nursing care planning tools that are task focused and may not consider patients’ psychological needs.

- The division in labour, with experienced nurses carrying out technical tasks such as administration of complex medication, and fundamental skills are delegated to unregulated healthcare assistants.

- Student nurses may be paired with healthcare assistants to learn fundamental nursing cares early in their undergraduate degrees.

- There is a lack of research evidence about the importance of fundamental care and a lack of clear definitions about what constitutes fundamental care.

We all need to challenge these barriers through valuing and developing evidence-based practice on how to deliver effective fundamental cares and changing organisational cultures for improved patient outcomes1. Consider Suzie scenario below.

Research on patients’ experiences of fundamental cares

The Fundamentals of Care Framework is being used as a template to explore patients’ experiences of care within various clinical settings and with different health conditions11-14. Patient populations include those after a stroke, admitted to intensive care, cancer patients, and patients with acute abdominal pain that resulted in hospitalisation. Narratives from these patients demonstrate how the three dimensions of physical, psychosocial and relational care are entwined within their experiences.

Findings included that:

- As patients strived to regain control of their life, the relationship with a nurse was essential.

- Their engagement with the nurse affected how fundamental cares were experienced.

- When patients felt a rapport with the nurse, and the nurse understood their individual needs, their fundamental care needs were met and this provided motivation in the recovery process11-12,14.

After a stroke patients identified the impact of their illness, particularly their loss of mobility, and how this affected managing fundamental cares. However, relationships developed with nurses were important in maintaining their dignity, privacy and self-esteem. Loss of independence and the emotional trauma of having to rely on others was hard to bear. Kitson et al14 (p. 398) noted:

“The loss of personal standards of hygiene, feeling unclean, smelling, having unkempt hair or not wearing their own clothes had been a humiliating experience for some people.”

Importantly, physical and psychosocial effects were linked, as the experiences of the physical problems had a profound effect on the patient’s psychosocial and emotional wellbeing. Therefore, for patients to experience dignified and integrated care all aspects of the Fundamentals of Care Framework need to be present throughout the caring process14. Interestingly some cancer patients, in contrast to patients post-stroke, described dignified care, when one nurse performed a simple act of washing attentively:

“…and she was really the only one that I felt at the time showed me really great kindness. She actually washed my legs and feet, which was wonderful, and just that very simple human touch and that very simple kindness of doing that made me feel so much better”13 (p.2327).

What enabled this nurse to overcome the barriers to demonstrate this caring?

Caring nurse-patient relationships for those undergoing surgery provided patients with feelings of safety:

“When nurses are calm and talk clearly, it makes me feel safe. When they show me that they care about me. It is the caring that is important. It is so important to feel that you are seen.”11 (p. 2316)

Conclusion

There is now renewed attention on how nurses can provide care that best meets patients’ and families’ needs in an integrated way. Dividing care into levels of basic and essential can have unintended consequences that do negatively affect patient experiences and outcomes. The Fundamentals of Care Framework provides nurses and nursing with a way to refocus on what elements of nursing care must be provided with the system level changes needed, together with the work that is related to diagnosis and treatment. It is only when these components come together that patient and whānau and family-centred care will eventuate.

View the PDF of this learning activity here >>

Establishing a positive nurse-patient relationship requires:

- Developing trust with patients

- Focusing on patients and giving them undivided attention

- Anticipating the patient’s needs

- Knowing enough about them to act appropriately

- Evaluating the quality of the relationship.

Recommended resources

- The International Learning Collaborative: http://intlearningcollab.org

- Point of Care Foundation: Their programmes help create open and compassionate organisational cultures and provide tools and support to bring about radical change within your workplace. www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk

- Why might good people deliver bad care? Yvonne Sawbridge argues that the caring professionals undertake hard, emotional labour which needs the same recognition by management that physical labour is given. www.youtube.com/watch?v=VC4FajTFpRU

About the Authors

- Claire Minton RN PhD is a nursing lecturer at Massey University, Palmerston North

- Lesley Batten RN PhD is a senior researcher at Massey University, Palmerston North

This article was peer reviewed by:

- Sue Wood RN MNS is the Quality & Patient Safety Director for Canterbury District Health Board and former director of nursing for MidCentral District Health Board.

- Sally Houliston RN MN is a Nurse Consultant (workforce development) at Hawke’s Bay District Health Board.

References

- FEO R, & KITSON A. (2016). Promoting patient-centred fundamental care in acute healthcare systems. International Journal of Nursing Studies 57, 1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.01.006.

- KITSON A, ATHLIN A, & CONROY T (2014). Anything but basic: Nursing’s challenge in meeting patients’ fundamental care needs. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 46(5) 331-339.

- World Health Organization. (2015). WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. Accessed 24 June 2018 from www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/global-strategy/en

- FEO R, ET AL (2017). Towards a standardised definition for fundamental care: a modified Delphi study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27 2285-2299. Doi:10.1111/jocn.14247

- KITSON A, CONROY T, KULUSKI K, LOCOCK L, & LYONS R (2013). Reclaiming and redefining the Fundamentals of Care: Nursing’s responses to meeting patients’ basic human needs. Retrieved 24 June 2018 from https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/75843/1/hdl_75843.pdf

- DELAUNE S, LADNER P, McTIER L, TOLLEFSON J, & Lawerence J. (2016). Australian and New Zealand Fundamentals of Nursing. Cengage Learning: Melbourne.

- FEO R, RASMUSSEN P, WIECHULA R (2017). Developing effective and caring nurse-patient relationships. Nursing Standard 31 (28) 54-63.

- JEFFS L, SARAGOSA M, MERKLEY J, & MAIONE M (2016). Engaging patients in meeting their fundamental needs: Key to safe and quality care. Nursing Leadership 29(1) 59-66.

- WHITTEMORE R (2000). Consequences of not “Knowing the Patient”. Clinical Nurse Specialist 14(2) 75-81.

- JACKSON D, & KOZLOWSKA O (2018). Fundamental care – the quest for evidence. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27 11-12. Doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14382

- JANGLAND E, TEODORSSON T, MOLANDER K, & MUNTLIN ATHLIN Å (2018). Inadequate environment, resources and values lead to missed nursing care: A focused ethnographic study on the surgical ward using the Fundamentals of Care framework. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27 2311-2321. Doi:10.1111/jocn.14095

- MINTON C, BATTEN L, & HUNTINGTON A (2018). The impact of a prolonged stay in the ICU on patients’ fundamental care needs. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27(11-12) 2300-2310. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14184.

- MUNTLIN ATHLIN Å, BROWALL M, WENGSTRÖM Y, CONROY T, & KITSON A L (2018). Descriptions of fundamental care needs in cancer care – an exploratory study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27:2322-2332. Doi: 10.111/jocn.14251

- KITSON A, DOW C, CALABRESE J D, LOCOC L, & ATHLIN Å M (2013). Stroke survivors’ experiences of the fundamentals of care: A qualitative analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50(3),392-403.