How soon should hip and knee replacement patients be up and mobile? Diane Alder reports on the research literature and her own master’s research findings after mobilisation on the day of surgery was introduced at her hospital.

A great deal of research in recent years has focused on the benefits of mobilising all patients as soon as possible after surgery. Mobilising after hip or knee replacement surgery (lower limb arthroplasty or LLA), however, has traditionally been delayed. But advancements in surgical and anaesthetic technique mean it is now not only safe to mobilise these patients earlier, but there is also evidence that there are many benefits in doing so.

Background

Arthrosis – the degeneration of a joint most commonly caused by osteoarthritis – is the leading reason for having joint replacement surgery or arthroplasty. Arthrosis is debilitating, often causing pain and disability and substantially reducing the quality of life of those affected.

The first attempts at joint replacement surgery happened more than 100 years ago, but only became effective in the 1960s (1,2). Hip and knee replacements (LLA) have become more common in the last two decades and, with our ageing population, demand will continue to grow (it is estimated that arthrosis affects 75 per cent of people over 65).

To meet this growing demand, researchers are looking at ways to reduce costs. Traditionally, LLA patients spent extended periods of time recovering in hospital. While length of stay has reduced for all types of surgery in the past 10 years, there is still a huge variability in length of stay globally after LLA, with ranges of 1–21 days (4).

A number of enhanced recovery programmes (ERPs) – also known as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) or ‘fast track’ protocols – have gained popularity in Europe and the US, with beneficial results for both LLA patients and providers (5). Many ERPs are expensive to implement, however, with entire units set up with increased staffing and equipment.

But while researching the barriers and opportunities for LLA patients in my own hospital (as part of a nursing research methods paper), I found one key component of many ERPs that I felt could be hugely beneficial as a stand-alone change: mobilising LLA patients on the day of surgery, not the day after. This became the focus of my master’s degree research. (Mobilising the day after surgery, i.e. day one, was standard when I began the study. See sidebar 1 for a summary of literature review findings on the benefits of early mobilisation of LLA patients.)

Introducing day of surgery mobilisation

Like many idealistic students, I wanted to carry out a randomised controlled trial to compare outcomes between day of surgery and day one mobilisers. However, my literature review revealed so many benefits in mobilising early, that I decided it would be unethical to make some patients stay in bed and not have the opportunity to benefit.

So, with the support of our surgeons and management at my 38-bed private surgical hospital in New Plymouth, I introduced an early mobilisation initiative for LLA patients as a quality improvement project. The initiative included developing a checklist so nurses could be confident that their patients were safe to mobilise (see checklist box). Three months later, after receiving ethics consent, I audited the discharged patient files for my master’s thesis and compared the outcomes of early mobilised LLA patients with the outcomes of patients mobilised on day one.

Exactly a year after the first audit, I conducted a follow-up audit. This was partly because uptake of the idea at the beginning was relatively slow, but gained support over the year as nurses and surgeons saw the benefits to patients. I also wanted to ensure that the gains were sustained (see sidebar 2 for audit results).

Conclusion

Many nurses were initially sceptical about mobilising LLA patients on the same day as their surgery. But the initiative soon gathered momentum when nurses saw for themselves their patients gaining independence earlier, with less pain and fewer adverse effects post-surgery.

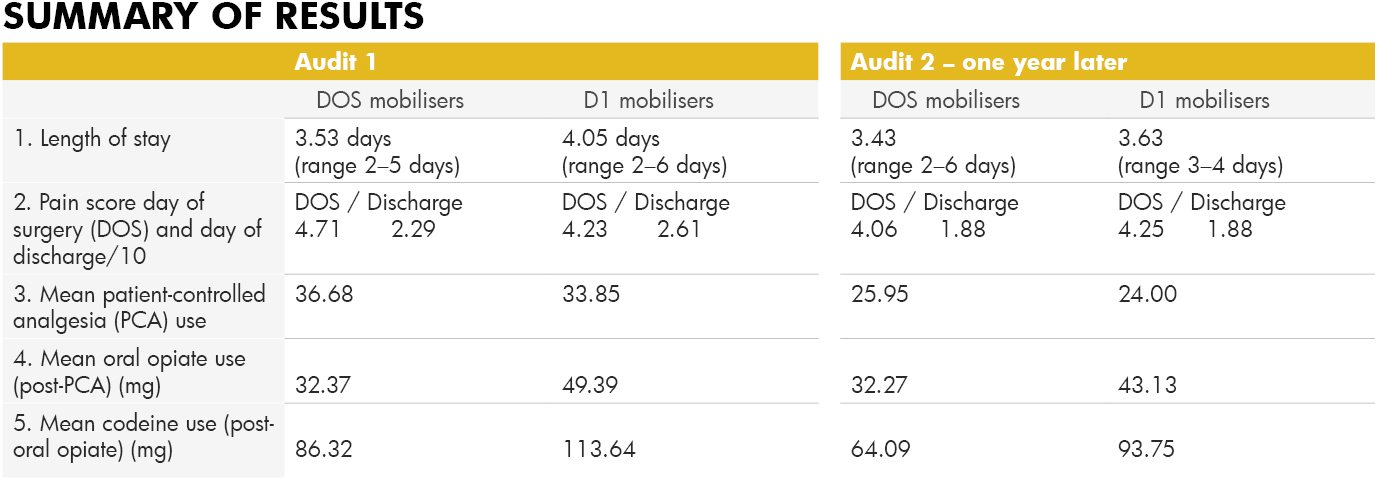

This change of heart was reflected in the audit results with only 56 per cent of LLA patients being mobilised successfully on the day of surgery in the first audit, compared with 84.6 per cent a year later.

While pain scores on the day of surgery were slightly higher on the day of surgery for early mobilisers, by the day of discharge their scores were lower, and less pain relief was used by early mobilisers during their stay, indicating lower pain levels. The length of stay decreased after the initiative and continued to decrease in the follow-up. Early mobilisation after LLA has now become the norm at our hospital as we continue to see improved outcomes for these patients.

*Author: Diane Alder Is a registered nurse at New Plymouth’s Southern Cross Hospital and completed a Master of Health Sciences degree last year.

Sidebar 1:

The benefits of early mobilisation of LLA patients

-

Less risk of venous-thromboembolism (VTE)

Patients mobilised the day of surgery are 30 times less likely to suffer from VTE complications (6).

-

Less pain

A number of studies show early mobilisers state lower pain scores overall (7,8,9). And the benefit isn’t just short-term; a German study found their early mobilisation group stopped taking analgesia altogether by day 41, while the traditional day one mobilisers continued to take analgesia for a further 30 days (10).

-

Less opiate pain relief required

Lower pain scores means less pain relief. One study showed a 60 per cent reduction in opiate use in the early mobilising group (6). Less opiate medication means a reduction in side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, so a reduced need for anti-emetics.

-

Less syncope

Often cited as a reason not to mobilise on the day of surgery, the risk of syncope is actually less likely to occur (6). Judicial intravenous fluid replacement and good pre-mobilising assessment is, of course, important.

-

Fewer blood transfusions

Fear of increased blood loss is also cited as a reason not to mobilise but early mobilisers actually have less need for blood transfusions – 9.8 per cent compared with 23 per cent (6,11).

-

Less joint stiffness

Joint stiffness can be associated with chronic pain following LLA. A Danish researcher found that early and intensive mobilisation helped to avoid the development of specific knee arthroplasty complications such as prolonged stiffness and delays in recovery of strength (12, 13).

-

Less mortality

Several large studies show that mortality reduces with ERPs that include early mobilisation (11,14,15).

-

Less time in hospital

Fifteen recent studies showed a reduced length of stay with ERPs; five of the studies isolated early mobilisation and studied its effect on length of stay. Results varied but 100 per cent had reduced length of stay for early mobilisers.

-

Increased quality of life/satisfaction

Most patients would prefer to be home, back to work or back to the golf course as soon as possible. A Danish study showed early mobilisers had increased quality of life/satisfaction (16).

-

Fewer infections

Many studies show shorter lengths of stay mean fewer infections, (8, 10, 17, 18). If a patient is able to mobilise to the toilet within hours of having LLA surgery, there is no need for an indwelling urinary catheter, removing the risk of catheter-induced UTIs. The less time a patient is in bed, the less chance of orthostatic pneumonia. And less time in hospital means a reduced likelihood of a hospital-acquired infection.

-

Fewer re-admissions

Early opponents to fast-track protocols argued that, if discharged too early, patients would just return as re-admissions. In fact, patients who mobilise earlier are far less likely to be re-admitted (4,19).

-

Economic benefits

There are huge savings to be made with reduced length of stay. Several studies have researched the economic benefits, citing savings of US$454,000 per annum in just one hospital in the US (20), €3.5 million in total per annum in Denmark (15), and £141 million in total per annum in the UK (11).

Side bar 2:

Early mobilisation New Zealand clinical audit

Audit 1: December 2015, following the introduction of an early mobilisation initiative for LLA patients in September 2015.

Subjects: n=52 (pre-initiative) + n=52 (post-initiative) = 104 patients, split into two groups; those that mobilised day of surgery (DOS) n=38; and those that mobilised day one (D1) n=66. Age range of patients was 51–92 years.

Audit 2: Follow-up audit. December 2016, one year later.

Subjects: n= 52, divided into DOS mobilisers n=44 and D1 mobilisers n=8.

Safety criteria checklist for early mobilisation

1. Patient is haemodynamically stable

● Blood pressure is stable, with systolic ≥ 100

● Heart rate is stable ≤ 100bpm

● Bleeding is minimal-moderate, if drain used then ≤ 50ml/hour

● Patient is not light-headed or short of breath at rest

2. Patient is neurovascularly stable

● Patient can actively plantar and dorsi flex ankles of both feet

● Patient can actively contract both quadriceps (doesn’t necessarily have to lift leg actively)

● Sensation can be reduced in operated leg, but not absent

3. Patient consent

Patient is alert and oriented and able to consent to mobilising

● Pain is controlled to level considered acceptable to patient at rest

REFERENCE LIST

- Wroblewski, B. M., Siney, P. D., & Fleming, P. A. (2006). The charnley hip replacement: 43 years of clinical success. Acta Chirurgiae Orthopaedicae et Traumatologiae Cechoslovaca, 73(1), 6-9.

- Mont, M., Jacobs, J., Lieberman, J., Parvizi, J., Lachiewicz, P., Johanson, N., & Watters, W. (2012). Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. (2011). The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 19(12), 768.

- Lilikakis, A. K., Gillespie, B., & Villar, R. N. (2008). The benefit of modified rehabilitation and minimally invasive techniques in total hip replacement. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 90(5), 406-411. doi:10.1308/003588408X285900

- Stambough, J. B., Nunley, R. M., Curry, M. C., Steger-May, K., & Clohisy, J. C. (2015). Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 30(4), 521-526. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.023

- Bandholm, T., & Kehlet, H. (2012). Physiotherapy exercise after fast- track total hip and knee arthroplasty: Time for reconsideration? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(7), 1292-1294. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.014

- Pearse, E. O., Caldwell, B. F., Lockwood, R. J., & Hollard, J. (2007). Early mobilisation after conventional knee replacement may reduce the risk of post-operative venous thromboembolism. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-British Volume, 89B(3), 316-322. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.18196

- Lunn, T. H., Kristensen, B. B., Gaarn-Larsen, L., & Kehlet, H. (2012). Possible effects of mobilisation on acute post-operative pain and nociceptive function after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 56(10), 1234-1240. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02744.x

- Labraca, N. S., Castro-Sanchez, A., Mataran-Penarrocha, G., Arroyo-Morales, M., Sanchez-Joya, M., & Moreno-Lorenzo, C. (2011). Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: Randomized clinical trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25(6), 557-566. doi:10.1177/0269215510393759

- Raphael, M., Jaeger, M., & van Vlymen, J. (2011). Easily adoptable total joint arthroplasty programme allows discharge home in two days. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia-Journal Canadien d Anesthesie, 58(10), 902-910. doi:10.1007/s12630-011-9565-8

- den Hertog, A., Gliesche, K., Timm, J., Muhlbauer, B., & Zebowski, S. (2012). Pathway-controlled fast-track rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized prospective clinical study evaluating the recovery pattern, drug consumption, and length of stay. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 32(8), 1153-1163. doi:10.1007/s00402-012-1528-1

- Malviya, A., Martin, K., Harper, I., Muller, S. D., Emmerson, K. P., Partington, P. F., & Reed, M. R. (2011). Enhanced recovery programme for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate: A study of 4,500 consecutive primary hip and knee replacements. Acta Orthopaedica, 82(5), 577-581. doi:10.3109/17453674.2011.618911

- Holm, B., Kristensen, M. T., Myhrmann, L., Husted, H., Andersen, L. O., Kristensen, B., & Kehlet, H. (2010). The role of pain for early rehabilitation in fast track total knee arthroplasty. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(4), 300-306. doi:10.3109/09638280903095965

- Husted, H., Jørgensen, C. C., Gromov, K., & Troelsen, A. (2015). Low manipulation prevalence following fast-track total knee arthroplasty: A multicenter cohort study involving 3,145 consecutive unselected patients. Acta Orthopaedica, 86(1), 86-91.

- Savaridas, T., Serrano-Pedraza, I., Khan, S. K., Martin, K., Malviya, A., & Reed, M. R. (2013). Reduced medium-term mortality following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty with an enhanced recovery programme: A study of 4,500 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthopaedica, 84(1), 40-43. doi:10.3109/17453674.2013.771298

- Khan, S. K., Malviya, A., Muller, S. D., Carluke, I., Partington, P. F., Emmerson, K. P., & Reed, M. R. (2014). Reduced short-term complications and mortality following enhanced recovery primary hip and knee arthroplasty: Results from 6,000 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthopaedica, 85(1), 26-31. doi:10.3109/17453674.2013.874925

- Larsen, K., Sorensen, O. G., Hansen, T. B., Thomsen, P. B., & Søballe, K. (2008). Accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation intervention for hip and knee replacement is effective: A randomized clinical trial involving 87 patients with 3 months of follow-up. (2008). Acta Orthopaedica, 79(2), 149-159. doi:10.1080/17453670710014923

- Tayrose, G., Newman, D., Slover, J., Jaffe, F., Hunter, T., & Bosco, J. (2013). Rapid mobilization decreases length-of-stay in joint replacement patients. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases, 71(3), 222-226.

- Wellman, S. S., Murphy, A. C., Gulcynski, D., & Murphy, S. B. (2011). Implementation of an accelerated mobilization protocol following primary total hip arthroplasty: Impact on length of stay and disposition. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 4(3), 84-90. doi:10.1007/s12178-011-9091-x

- Robbins, C. E., Casey D., Bono, J. V., Murphy, S. B., Talmo, C. T., & Ward, D. M. (2014). A multidisciplinary total hip arthroplasty protocol with accelerated postoperative rehabilitation: does the patient benefit? The American Journal of Orthopedics, 43(4), 178-181.

- Chen, A. F., Stewart, M. K., Heyl, A. E., & Klatt, B. A. (2012). Effect of immediate postoperative physical therapy on length of stay for total joint arthroplasty patients. Journal of Arthroplasty, 27(6), 851-856. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.01.011