“A nurse must be a woman, working not in the first place for the sake of money-making, but for the good of her fellow creatures to alleviate suffering when she can and help towards health those who need her care.”

This 1909 statement from Hester Maclean, our country’s first chief nurse, could probably take pride of place as Exhibit A when arguing the case that a nurse’s monetary worth has historically been undervalued because of the association with ‘womanly’ qualities.

Such evidence might be needed after the NZNO lodged a pay equity claim in June for nurses working in DHBs as part of its bargaining talks. Pay equity claims are said to have merit if the work is performed predominantly by women; there are ‘reasonable grounds’ to believe the work has been historically undervalued because it uses skills or qualities ‘generally associated with women’; and the work continues to be subject to gender-based undervaluation.

Nobody is expecting such a claim to be settled quickly, particularly as the shockwaves from the historic pay equity settlement for caregivers are still being worked through, particularly by nurses in the residential aged care sector who have lost pay relativity with their unregulated co-workers (see story last edition).

But NZNO sees the pay equity claim as the first page in the final chapter of closing the gender pay cap for its DHB nurses (and other members) and, eventually, nurses beyond the public health sector.

The union argues that, unlike the 2005 Fair Pay settlement, this time around the Kristine Bartlett vs TerraNova pay equity settlement is creating not only a legal precedent but also a legislative framework to pursue and settle pay equity claims (although unions are not happy with the current wording of the draft bill introducing that framework).

It is also acknowledged that the pay equity process will take time, with NZNO industrial services manager Cee Payne writing in Kai Tiaki recently that eliminating the gender pay gap would “most likely take the next decade to be fully realised”.

“Not for the sake of money-making”

Our formidable first matron-in-chief and chief nurse Hester Maclean’s belief that nurses should put caring before commerce set the culture for much of the first half of the 20th century.

Nursing shortages in World War II saw a revised salary scale negotiated and a salaries advisory committee for public hospitals set up in 1947, but as the country settled back into peacetime nurses lost industrial traction, with little salary movement for nearly two decades. Nursing was once again seen as a feminine vocation not to be marred by talk of money.

In 1957 the New Zealand Nurses Association (the forerunner of today’s NZNO) even withdrew from the Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity for fear that the professional organisation might become “too political”.

But times were changing and in 1962 international advice was sought by the association on better methods for negotiating pay and conditions, leading in 1965 to the introduction of overtime and weekend penal rates – the first real pay rise since 1950 – and the replacement of the salaries advisory committee with an arbitration mechanism in 1969.

The 1970s saw public hospital nursing unionised, but it wasn’t until 1985 with the ‘Nurses are worth more’ campaign that nurses really tried to use industrial clout and public opinion to seek fairer pay, including marching on parliament for the first time. In an even bigger first, in 1989 nurses took strike action for the first time, followed soon after by a decade of health restructuring and industrial reform that saw nursing go into survival mode for much of the 1990s.

Pay jolt and pay gaps between sectors

With the new millennium and the return of national bargaining, nurses were again ready to look at the issue of pay equity. On Suffrage Day 2003, NZNO launched its ‘Fair pay – because we’re worth it’ campaign to gain pay parity for DHB nurses with teachers and police. After a hard-won campaign to get such a deal funded, a settlement was reached, leading to ratification in early 2005 of a national DHB multi-employer collective agreement (MECA) that introduced an up to 20 per cent pay jolt for nurses.

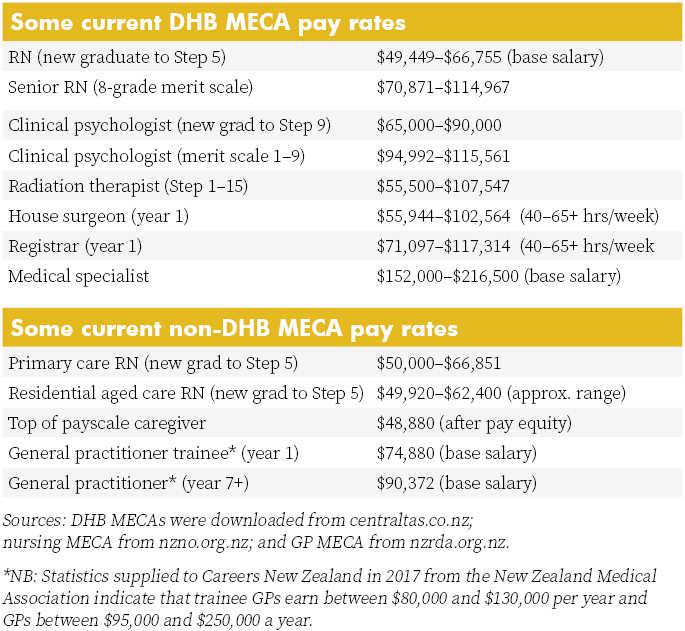

That pay jolt created a gap between DHB nurses and many of their non-DHB nursing colleagues. A decade later, that pay gap is nearly closed for nurses covered by MECAs in sectors such as primary health, family planning and prisons.

But the pay gap still remains for nurses with less industrial clout, including nurses in residential aged care, whose take-home pay is on average 23 per cent lower than their colleagues in public hospitals. And some nurses working for Māori and iwi providers are earning up to 20 per cent less than colleagues working for similar primary healthcare services. Those pay gaps are thrown into even starker relief by the realisation that the caregiver pay equity settlement could see the pay gap between nurses in those sectors and their unregulated colleague shrink or even disappear.

NZNO believes that the best step toward pay equity for all nurses is to begin by negotiating in the DHB sector, where it has the greatest numbers and influence. The State Services Commission and Combined Trade Unions (CTU) had also agreed that unions in the public sector could lodge pay equity claims through collective bargaining using the principles agreed by the tripartite Joint Working Group on Pay Equity late last year.

This led to NZNO lodging its claim when talks began in June, rather than waiting for the progress of the draft Employment (Pay Equity and Equal Pay) Bill, which NZNO and other unions oppose in its current form, saying it takes a backward step by placing new and “unreasonably onerous” requirements on women taking claims.

Meanwhile, once NZNO and the DHBs agree on terms of reference for pay equity talks, the task of assessing, with a gender-neutral eye, the value of nursing work in terms of skill, knowledge, responsibility, effort and working conditions will begin. Then comes selecting historically male-dominated occupations of equal value as comparators to back the claim that nurses are underpaid because of historic and ongoing gender inequity.

Hester Maclean might not approve, but it is probably about time that the value of a nurse “working for the good of her [his] fellow creatures” was calculated once and for all.

Lessons learnt from midwives’ pay equity case?

Community midwives lodged an historic pay equity claim under the Bill of Rights Act in 2015 and found that proving gender inequity was far from simple.

The College of Midwives’ claim for its self-employed lead maternity carers (LMC) led to mediation in 2016 with funder the Ministry of Health. In May this year it withdrew its court action after winning an interim pay increase and a legally binding agreement from the ministry that midwives would work with officials to design a new funding model for midwifery-led care that resolved the college’s longstanding concerns about pay equity and working conditions.

But in a report to members, the college said that after putting thousands of hours and dollars into researching and providing more than 3,000 documents for the case, it had proven easier to prove that midwifery pay was inequitable than it was to legally prove that inequity was due to gender.

LMC midwives had fought a case for equal pay for work of equal value in 1993 through the Maternity Benefits Tribunal and won, but there had been only two small increases since 2007, raising questions as to whether midwifery funding provided a sustainable income for the 24-hour, on-call service.

The midwifery case was unique because, as self-employed health professionals, community midwives were not covered by the Employment or Pay Equity Acts. But they too went through the process of looking at the historic discrimination of a female-dominated ‘caring profession’ and seeking out comparators in historically male-dominated professions. So are there lessons to share?

Alison Eddy, a midwifery advisor for the College of Midwives, says proving that a profession’s pay is inequitable because of gender is potentially difficult. She says it is easier to measure the clinical and technical skills and the professional accountability required of nurses and midwives than the so-called ‘soft skills’ that are also key to both female-dominated professions. The skills such as building relationships, working alongside people, and empowerment are all areas that can potentially be undervalued.

Commodifying those skills in order to match and compare pay with a comparator occupation in a field that has been historically male-dominated can also be challenging. Eddy says that after going through a lengthy process of using equitable job evaluation tools, the midwifery case had opted for pharmacists and GPs as two potential comparators and decided that midwifery fitted somewhere above the role of pharmacist and slightly below the role of GP.

Under the agreement with the ministry was the commissioning of an independent evaluation of the midwifery role and the provision of comparators and a market value for the role, using a gender-neutral lens, in readiness for a new funding model being in place by July 2018.

However, Eddy says that there are real concerns that the numbers now leaving the midwifery workforce due to feeling undervalued could impact on the sustainability of the service.