Patients from minority ethnic groups experience challenges in the healthcare system resulting from cultural and language factors. This article looks at some of the challenges that multicultural patients can experience as in-patients and suggests some strategies to help minimise those challenges.

By Krinessa Valenzuela and Monina Hernandez

________________________________________________________________________

Reading this article and undertaking the learning activity is equivalent to 60 minutes of professional development.

Learning outcomes

Reading and reflecting on this article will help nurses to:

- Increase awareness of the challenges multicultural patients experience as inpatients.

- Identify the barriers that affect the health outcomes of multicultural patients.

- Identify strategies or interventions to remove the barriers.

The learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council competencies 1.5, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.6 and 3.2.

________________________________________________________________________

INTRODUCTION

New Zealand is an ethnically diverse society and is set to become more so, with record levels of net migration in the past five years.

In Census 2013, the major ethnic groups in New Zealand were European (74 per cent); Māori (14.9 per cent); Asian (11.8 per cent); Pacific (7.4 per cent); and Middle Eastern/Latin American/African – also abbreviated as MELAA (1.2 per cent)1.

Multicultural populations require a healthcare system that provides culturally safe care. Culture and language barriers have a big impact on health outcomes for patients from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. Understanding the patient’s experiences, identifying their challenges and implementing strategies to help solve these challenges ensures that patients receive culturally safe nursing care, disparity is reduced and good health outcomes are achieved.

LOCAL CASE STUDIES

This article draws on the authors’ own case study research, which is aimed at helping nurses understand the in-patient experiences of patients belonging to CALD groups in New Zealand and identifying strategies to support patients and their families during their hospital stay. The case studies involved patients from CALD backgrounds who received care at the coronary care unit of a district health board hospital between April and May 2018.

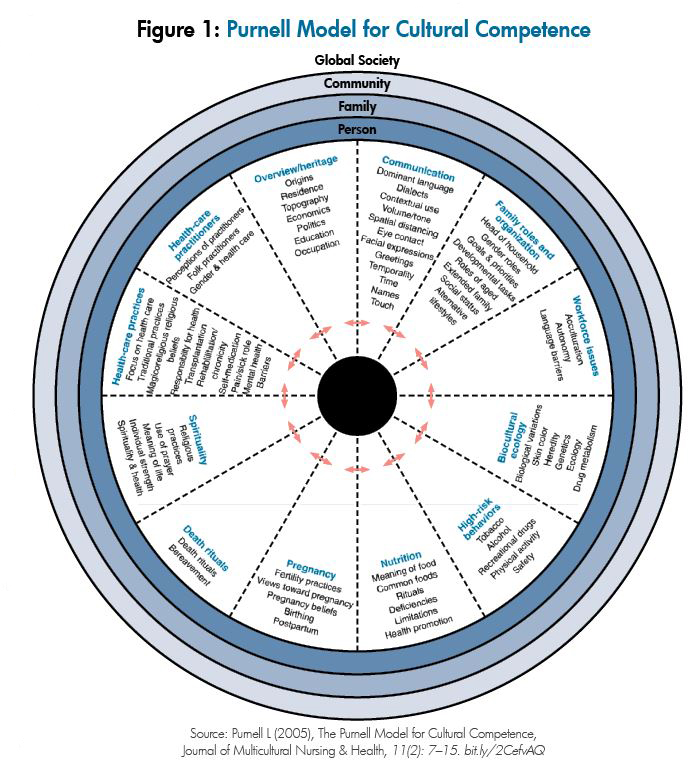

Three themes emerged from interviewing the coronary care patients using Purnell’s Model of Cultural Competence (see Figure 1). These are: the importance of family; views about illness and its impact on their lives; and barriers in accessing healthcare services.

The importance of family

Patients from collective cultures value family involvement and engagement in their care. The first theme that emerged from the interviews was the importance of family support in the care of a sick family member.

“Children and grandchildren look after the loved ones.”

Mr VM, 67, ventricular fibrillation arrest, Tongan.

“To look after the elder, it is important.”

Son of Mrs VN, 80, end-stage IHD, Indian.

Looking after family members was central to the patients interviewed, who were from Tongan, Samoan, Indian and Serbian backgrounds.

“It is better for us to look after the sick at home so they don’t feel lonely in the hospital.”

Mr VM, 67, VF arrest, Tongan.

“Always stay with the sick. We look after the sick.”

Son of Mrs VN, 80, end-stage IHD, Indian.

Extended family also play an important role in looking after sick family members.

It [extended family] is important. Grandkids look after their grandparents.”

Mr O, 60, NSTEMI, Samoan.

Family support is important in providing patients from CALD groups with physical and emotional support while in hospital2.

Views about the illness and its impact on their lives

Cultures have different ways of understanding illness and may attribute different causes to the origin of their symptoms. How illness is explained is strongly influenced by families’ cultural and religious backgrounds. Patients’ views about disease causation and how it impacts on their lives vary.

One patient attributed his illness to a higher power.

“It [illness] is a way God

teaches you sometimes in life;

a wake-up [call] from God”

Mr VM, 67, VF arrest, Tongan.

Whereas another attributed it to lifestyle.

“The first reason is smoke. Then after 15 years, illness comes. Second is food; I eat anything.”

Mr S, 60, STEMI – PCI to LAD, Serbian.

“Keep rules, restrict – no fats,

stop smoking, exercise.”

Mr S, 60, STEMI – PCI to LAD, Serbian.

Some of the patients displayed feelings of contentment even when they were sick.

“I’m better, I’m happy.

Everything is in my hands now.”

Mr S, 60, STEMI – PCI to LAD, Serbian.

BARRIERS TO ACCESSING HEALTHCARE SERVICES

Patients’ views and explanations of their illnesses affect the way they respond to and manage them. In addition to the wider systemic barriers, language and cultural issues are the two most widely experienced barriers to service utilisation3, 4.

Patients identified several barriers in accessing healthcare services. Migrants from CALD backgrounds may be unfamiliar with New Zealand health services and how to access them. One patient saw the need for advertising healthcare services to the Samoan community.

“Some people do not know how to access health care. Public should be aware what services are available. Broadcast services.”

Mr O, 60, NSTEMI, Samoan.

Another patient identified language as a barrier and also the concerns that patients may have about their privacy and confidentiality when interpreters are used.

“The difficulty is the language barrier. The problem with the translator is that she will not say the same thing to the translator that she will say to me.”

Son of Mrs VN, 80, end-stage IHD, Indian.

Patient insights in the interviews about barriers to accessing healthcare services highlight a number of areas for improvement. The first is the need for translated information in relevant languages delivered through ethnic media, such as radio stations and newspapers. Targeted and tailored health education needs to be available to ethnic communities.

The second is patient’s concerns about their maintaining privacy and confidentiality when professional interpreters are used. Confidentiality becomes an issue, particularly in smaller communities. Patients may be reluctant to use an interpreter because they know the interpreter or have fears that their medical information will be made public. At the beginning of a consultation, it is important to reassure the patient and their family that the health practitioner and the interpreter will respect the patient’s rights to confidentiality.

HEALTH CARE CHALLENGES AMONG CALD GROUPS

Patients from CALD groups may face psychological stress, treatment barriers, language barriers, challenges with informed consent, and the risk of adverse events when there are communication difficulties.

Psychological stress

The stresses that CALD patients experience are not just physical in nature but also psychological5. For any patient, illness can be a major stressor, but for patients from CALD backgrounds, the stress may be exacerbated by communication difficulties.

In particular, patients with limited or no English language experience anxiety and powerlessness because of their inability to communicate with health practitioners2.

Even with the use of interpreters, the patient may feel stressed as they may not feel fully understood. Moreover, the problem with communication causes stress not only to patients but also to healthcare providers6. For this reason, knowing how to work with interpreters – including how to pre-brief and debrief when using an interpreter for a consultation – is an important skill for health practitioners to gain.

Treatment barriers

Besides the psychological stress that the patients may experience while in the hospital, they may also encounter treatment challenges.

A CALD patient is more likely to refuse treatment7. Treatment refusal may be due to the patient’s inability to understand their illness and the treatment offered2, 8. Treatment refusal can lead to non-adherence with prescribed treatment plans, longer hospital stays and increased risks of readmission compared with English-speaking patients9. Communication problems also lead to treatment delays10.

Patients who have limited or no English language require an interpreter before they can make decisions regarding treatment. This may delay treatment, including procedures where the patient is required to follow instructions, such as X-rays and surgical procedures. Successful treatment requires good communication between the health practitioner, the patient and their family5, 11.

Language barrier

Good cross-cultural communication is important for health practitioners and patients to understand each other. Health practitioners need to assess, for example, whether patients are using traditional remedies or herbal medicines. Patients need to understand their illness and the treatment being offered. In acute care settings, health practitioners must utilise professional interpreters, where needed, to help them communicate effectively.

However, some studies prove that errors in transmitting information still occur even with the utilisation of professional interpreters12. This often occurs when the health practitioner is not trained in how to work with an interpreter and is not in control of the interpreting session.

Underutilisation of interpreters has also been reported in the literature13. It is sometimes easier to not utilise interpreters for patients who can speak basic English. However, this may lead to major impacts on the patient’s health outcome14. Sometimes bilingual staff are accessed as interpreters; however, because of the lack of professional training, errors such as omissions, addition, substitution and condensation of information occur8.

Patients who require interpreters have problems with taking in and remembering information15. It is therefore important to ensure that patients get adequate support from the healthcare team to ensure that correct and adequate information is provided for successful care and discharge.

Challenges with informed consent

Communication is also important when patients provide informed consent. Since informed consent is legal in nature10, patients should understand what they are consenting to. The transfer of information should be clear and accurate.

When medical information regarding a necessary procedure is given to a patient, it is critical for informed consent that they understand and agree to what the health practitioner is communicating to them. It is difficult enough at times to obtain informed consent from an English-speaking patient, but it is much more so from those who speak no or limited English.

In such cases, interpreters play an essential role. Regardless of the language spoken, informed consent is a patient’s right and healthcare providers need to ensure that this process is managed competently and professionally.

Adverse events

CALD patients are at risk of adverse events when there is a language barrier between themselves and the health professional. Diagnostic and medication errors are examples of adverse events9, 16, 17. Non-English-speaking patients may struggle to understand medical terms in English18, which may directly affect the quality of services they receive and their timely access to services18, 19. These patients are disadvantaged in accessing health services equitably with other groups due to the cultural and linguistic barriers discussed8. Healthcare practitioners can improve the quality of care that CALD groups receive by gaining the knowledge, attitudes and skills needed to become culturally competent.

STRATEGIES TO REDUCE THE HEALTHCARE CHALLENGES

There are ways to help reduce the challenges faced by minority ethnic groups in health care. These include promoting and practising cultural competence and safety among healthcare providers, using professional interpreters, and encouraging family support.

Providing culturally competent care

Cultural competence can be defined as developing an awareness of one’s own existence, sensations, thoughts and environment without letting it have an undue influence on those from other backgrounds; demonstrating knowledge and understanding of the client’s culture; accepting and respecting cultural differences; adapting care to be congruent with the client’s culture (Purnell, 1998)20.

Providing culturally competent care is a way to reduce barriers to accessing healthcare services for CALD patients18. Practitioners’ abilities to engage patients and their families and to assess and understand their explanatory models of health and illness will contribute to good health outcomes for the patients6, 16, 21.

Developing cultural competence

Campinha-Bacote and Munoz (2001)22 proposed a five-component model for developing cultural competence, which is outlined as follows:

- Cultural awareness involves self-examination of in-depth exploration of one’s cultural and professional background. This component begins with insight into one’s cultural healthcare beliefs and values. A cultural awareness assessment tool can be used to assess a person’s level of cultural awareness.

- Cultural knowledge involves seeking and obtaining an information base on different cultural and ethnic groups. This component is expanded by accessing information offered through sources such as journal articles, seminars, textbooks, internet resources, workshop presentations and university courses.

- Cultural skill involves the nurse’s ability to collect relevant cultural data regarding the patient’s presenting problem and accurately perform a culturally specific assessment. The Giger and Davidhizar model23 offers a framework for assessing cultural differences in patients.

- Cultural encounter is defined as the process that encourages nurses to directly engage in cross-cultural interactions with patients from culturally diverse backgrounds. Nurses increase cultural competence by directly interacting with patients from different cultural backgrounds. This is an ongoing process; developing cultural competence is a journey.

- Cultural desire refers to the motivation to become culturally aware and to seek cultural encounters. This component involves the willingness to be open to others, to accept and respect cultural differences, and to be willing to learn from others.

The disparities that arise due to cultural factors make cultural competence a priority in health care24. But there is no simple formula for solving cultural issues and establishing plans in delivering culturally competent nursing care. When challenging cultural issues arise, nurses might like to discuss and consult with senior colleagues and management to ensure that such issues can be resolved in the best interest of the patient.

Using trained interpreters

Using trained interpreters, rather than family members or bilingual staff, is important10 as it ensures that correct information is being relayed to patients, reduces the risk of errors and leads to improved health outcomes16. The importance of using trained health professionals to ensure good cross-cultural communication and safe, effective care for non-English-speaking patients is also highlighted in this article.

Extended family provides support

“To look after the elder, it is important.”

Son of Mrs VN, 80, end-stage IHD, Indian.

It is important to recognise the role of extended family in the care and support of the sick in collective cultures18. Knowing how to engage with family members, to work with the decision-makers and to communicate respectfully is an essential part of building trust and rapport.

The family will expect to be engaged and consulted and will play a significant role in decision-making for those who are sick2. Family members may advocate for the sick member, facilitate communication among healthcare providers, as well as provide basic care2. They may also communicate the sick member’s fears, needs and feelings to the health practitioner2. Encouraging family support in the care of patients from CALD groups is recommended.

Patients’ and families’ cultural and religious beliefs and practices should also be included in treatment regimes where practicable and safe16.

CONCLUSION

Providing culturally competent and safe care to all patients is an essential nursing responsibility. Due to the growing number of patients from CALD groups – and the challenges and barriers they experience in the healthcare setting – it is important for nurses to practice cultural competence, to use professional interpreters, and to encourage family support. It is essential for nurses to reflect on the experiences of their cross-cultural interactions with patients and their families’ experiences, as well as the cultural knowledge and skills needed to ensure that quality care can be provided for CALD patients at all times.

View the PDF of this learning activity here >>

___________________________________________________________

About the authors:

- Krinessa Valenzuela, RN, BSciNsg, PGDip gained her nursing degree at the University of the Philippines and currently works in the coronary care unit of Hutt Hospital HVDHB while studying for her Master of Nursing.

- Monina Hernandez, RN, BSN, MNur (Hons) is a lecturer at the School of Nursing, Massey University.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- Annette Mortensen, RN, PGDipEd, MPhil (Nursing), PhD, project manager research and development for eCALD services at Waitemata DHB.

- Jenny Song, RN, BN (Wintec), PGDip (Nursing), Bachelor of Medicine (Xuzhou),

a senior academic staff member at Wintec’s Centre for Health and Social Practice.

RECOMMENDED RESOURCES:

- eCALD: the Ministry of Health-funded eCALD service provides free, accredited e-learning courses for health professionals working with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) groups in New Zealand, including working with interpreters: www.ecald.com/courses/cald-cultural-competency-courses-for-working-with-patients.

- Cultural awareness assessment tool: a simple, 17-question tool for gauging a nurse’s cultural awareness from Catalano’s Nursing Now: Today’s Issues, Tomorrow’s Trends. Available online at bit.ly/2oUDQC1.

- Cultural assessment model: key components of the Giger and Davidhizar cultural assessment model23 for assessing cultural differences in patients can be viewed at bit.ly/2O3rzGn.

- Working with interpreters for primary care practitioners: an e-learning module developed by the University of Otago: https://www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/e-learning/arch/story_html5.html

Nursing Council definition of cultural safety:

The effective nursing practice of a person or family from another culture, and is determined by that person or family. Culture includes, but is not restricted to, age or generation; gender; sexual orientation; occupation and socioeconomic status; ethnic origin or migrant experience; religious or spiritual belief; and disability.

The nurse delivering the nursing service will have undertaken a process of reflection on his or her own cultural identity and will recognise the impact that his or her personal culture has on his or her professional practice. Unsafe cultural practice comprises any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well being of an individual.

References

- STAT NZ (2013). 2013 Census quick stats bout culture and identity. Retrieved July 2018 http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-culture-identity/ethnic-groups-NZ.aspx

- GARRETT P, DICKSON H & WHELAN A (2008). What do non-English-speaking patients value in acute care? Cultural competency from the patient’s perspective: A qualitative study. Ethnicity & Health13(5) 479-496.

- MEHTA S (2012). Health Needs Assessment of Asian People Living in the Auckland region. Auckland: Northern DHB Support Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.countiesmanukau.health.nz/assets/About-CMH/Performance-and-planning/health-status/2012-health-needs-of-asian-people.pdf

- STATISTICS NEW ZEALAND AND MINISTRY OF PACIFIC ISLAND AFFAIRS (2011). Health and Pacific peoples in New Zealand.Wellington: Statistics New Zealand and Ministry of Pacific Island Affair. Retrieved from: http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/pacific_peoples/pacific-progress-health.aspx

- LEE T, SULLIVAN G & LANSBURY G (2006). Physiotherapists’ communication strategies with clients from culturally diverse backgrounds. Advances in Physiotherapy8(4) 168-174.

- COLEMAN J & ANGOSTA A (2016). The lived experiences of acute-care bedside registered nurses caring for patients and their families with limited English proficiency: A silent shift. Journal of Clinical Nursing26 678–689.

- NELSON A (2002). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of the National Medical Association 94(8) 666-668.

- HEANEY C & MOREHAM S (2002). Use of interpreter services in a metropolitan healthcare system. Australian health review: A publication of the Australian hospital association25(3) 38-45.

- WU M & RAWAL S (2017). ‘It’s the difference between life and death’: The views of professional medical interpreters on their role in the delivery of safe care to patients with limited English proficiency. Plos One(10) doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185659.

- GARLOCK A (2016). Professional interpretation services in health care. Radiologic Technology88(2) 201-204.

- VAN ROSSE F, DE BRUIJNE M, SUURMOND J, ESSINK-BOT M et al (2016). Language barriers and patient safety risks in hospital care: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 54 45-53.

- FLORES G (2005). The Impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of healthcare: A systematic review. Medical Care Research and Review 62(3) 255-299.

- SEERS K, COOK L, ABEL G, SCHLUTER P et al (2013). Is it time to talk? Interpreter services use in general practice within Canterbury. Journal of Primary Health Care 5(2) 129.

- ISAAC K (2001). What about linguistic diversity? A different look at multicultural health care. Communication Disorders Quarterly 22(2)110-113.

- LIPSON-SMITH R, HYATT A, MURRAY A, BUTOW P et al (2018). Measuring recall of medical information in non-English-speaking people with cancer: A methodology. Health Expectations21(1) 288-299.

- DAVIES S, DODD K & HILL K (2017). Does cultural and linguistic diversity affect health-related outcomes for people with stroke at discharge from hospital? Disability & Rehabilitation39(9) 736-745.

- SCHYVE P (2007). Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: The joint commission perspective.Journal of General Internal Medicine22(2) 360–361.

- TRUONG M, GIBBS L, PARADIES Y & PRIEST N (2017). “Just treat everybody with respect”: Health service providers’ perspectives on the role of cultural competence in community health service provision. ABNF Journal28(2) 34-43.

- THOMPSON D (2002). Cultural aspects of adjustment to coronary heart disease in Chinese-Australians: A review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing39(4) 391-399.

- PURNELL L (2013). Transcultural Health Care: A Culturally Competent Approach. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company

- BRACH C & FRASER I (2000). Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Medical Care Research and Review57(14)181-217.

- CAMPINHA-BACOTE J & MUNOZ C (2001). A guiding framework for delivering culturally competent services in case management. The Case Manager, 12(2), 48-5.

- GIGER J & DAVIDHIZAR R (2002). The Giger and Davidhizar transcultural assessment model. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13, (2) 185-188.

- CAMPINHA-BACOTE J (2002). The Process of Cultural Competence in the Delivery of Healthcare Services: A Model of Care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing13 (3) 181–184.