This learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council registered nurse competencies 1.1, 1.4, 2.1-2.4, 2.6, 2.8-2.9.

Learning outcomes

Reading and reflecting on this article will enable you to:

- further your understanding of how the quality of clinical service delivery is measured in your workplace

- review your understanding of skin tear injuries and their significance for the individual concerned.

Introduction

Henry had been living in an aged residential care facility for several years. He was now frail and confused, requiring assistance with almost all aspects of daily living. Paul, Henry’s son, visited him at least twice weekly, and on a recent visit noticed that his lower arm was bandaged. Staff were unable to tell Paul what had happened to Henry’s arm, and there was no wound assessment or treatment plan. According to the wound register, Henry had two other skin tears on his legs, but the status of these wounds was unclear.

When the registered nurse removed Henry’s arm bandage, two large and inflamed skin tears (each with a partial flap loss) were found. Skin closure strips had been used on both injuries and then covered with dry dressings, which had adhered to the wounds. Henry moaned loudly and kept trying to move his arm away when the areas were being redressed1.

Although skin tears represent more than half of all skin injuries in older adults, they have been described as forgotten wounds2, receiving little attention or research.

Skin injuries such as skin tears are often regarded as inevitable, and remain underappreciated, under-reported and essentially invisible3. Yet nurses working with older adults in all clinical settings are likely to encounter skin tears on a very regular basis.

The factors that contribute to the quality of nursing service delivery for older adults are complex, and singling out just one measure alone cannot offer a valid representation of the quality of service delivery. However exploring events and injuries such as skin tears in more depth enables clinical staff and management to identify opportunities for improving service delivery and reducing potential/actual distress and injury for older adults.

Skin tears revisited

Skin tears are “wounds caused by shear, friction, and/or blunt force, resulting in separation of skin layers. A skin tear can be partial thickness (separation of the epidermis from the dermis) or full thickness (separation of both epidermis and dermis from underlying structures)”4. (Refer to the STAR Skin Tear Classification System [see Box 1 Next page]5 and the learning activities associated with this article for further information on skin tear classifications and management). Although there are a number of commonly recognised classification tools for assessing and documenting skin tears, international research suggests these are not used regularly6.

Internationally, information on the skin tear prevalence and incidence rates are limited2. It has been suggested that under-reporting occurs because of a primary focus on pressure injuries, and that iatrogenic skin injuries, such as skin tears, and incontinence-associated dermatitis, are regarded as an inevitable part of ageing3. The New Zealand prevalence rate (number of new and current skin tears) is unknown7.

ACC accepts claims for primary injuries that include skin damage, injury or tears related to treatment by a registered health practitioner, but it cannot provide data specific to skins tears. Between 2011 and 2016 the number of accepted treatment-related claims for skin damage, injury or tears varied between 161 and 239 per year, with an average of 181 claims per year.

Since data was collected in 2005, 79 per cent of accepted claims for this primary treatment injury relate to individuals aged over 65 years of age. Nursing is the lead ‘context’ of these injuries and the top three treatment events that resulted in the injury are firstly removal of dressings/wound care; secondly patient transfer, and lastly removal of strapping8.

Australian researchers identified an incidence rate of 10.6 per 1,000 occupied bed days in their control group of residents in aged care facilities, while another study identified a 20 per cent prevalence rate in adults aged over 80 years living in the community9.

The skin of older adults is particularly vulnerable to injury, and iatrogenic skin injuries result from complex, multifactorial and interconnected threats3. Tissue tolerance is affected by:

- advancing age

- pre-existing health status and comorbidities

- level of nutrition

- medications

- perfusion

- oxygenation

- mobility

- sensory perception3.

Environmental factors, such as staff turnover, skill mix, and knowledge and care practices all have the potential to exacerbate skin tear rates.

Skin tear outcomes

Skin tears range from relatively minor to extensive and complex wounds, although they may be perceived by some as minor injuries10. Like any wound, they are a potential site of infection, especially in the frail elderly, as well as impacting on the person’s quality of life. Skin tears can be painful, as the superficial nerve endings are usually affected10 and have the potential to become chronic wounds.

The management of skin tear injuries further adds to staff workloads and care delivery costs. When older adults experience skin tears on a regular basis, keeping track of multiple injuries and their healing status can prove challenging. This is especially so when these wounds may not require daily changes of dressing if appropriate dressings are used, meaning there is an increased potential for them to be overlooked.

The experience of a skin injury, such as a skin tear, is unique and specific to each individual injury, and can impact on all aspects of the person’s wellbeing3. Ongoing skin tears can be a very visible and unwelcome reminder for both individuals and their families of physical deterioration. When a person experiences multiple skin tears over time, they also have the potential to cause family members to question the quality of service delivery.

BOX 1

STAR Skin Tear Classification System Guidelines

- Control bleeding and clean the wound according to protocol.

- Realign (if possible) any skin or flap.

- Assess degree of tissue loss and skin or flap colour using the STAR Classification System.

- Assess the surrounding skin condition for fragility, swelling, discolouration or bruising.

- Assess the person, their wound and their healing environment as per protocol.

- If skin or flap colour is pale, dusky or darkened reassess in 24-48 hours or at the first dressing change.

STAR Classification System

1. Category 1a

A skin tear where the edges can be realigned to the normal anatomical position (without undue stretching) and the skin or flap colour is not pale, dusky or darkened.

2. Category 1b

A skin tear where the edges can be realigned to the normal anatomical position (without undue stretching) and the skin or flap colour is pale, dusky or darkened.

3. Category 2a

A skin tear where the edges cannot be realigned to the normal anatomical position and the skin or flap colour is not pale, dusky or darkened.

4. Category 2a

A skin tear where the edges cannot be realigned to the normal anatomical position and the skin or flap colour is pale, dusky or darkened.

5. Category 3

5. Category 3

A skin tear where the skin flap is completely absent.

From: STAR Skin Tear Classification Tool developed by Skin Tear Audit Research (STAR). Silver Chain Group Limited, Curtin University. Revised 4 February 2010. Reprinted August 2012. You can download full STAR tool and glossary at: www.woundsaustralia.com.au/wa/resources.php

Is our service up to standard?

Measuring the quality of care is a complex and multifaceted undertaking.

All healthcare services in New Zealand are regularly assessed against the Health and Disability Sector Standards (2008)11. Compliance with these standards includes having a plan for measuring the quality of services, which may involve monitoring quality indicators (see Box 2), complaints, service user satisfaction surveys, and responses to identified issues.

New Zealand’s Health Quality and Safety Commission12 has developed a set of quality markers that track progress over time in the health and disability sector relating to four key priority areas – falls, healthcare associated infections, surgical harm and medication safety.

A Standards New Zealand Working Party developed specific clinical indicators for individuals requiring aged care or dementia care in 2005 (see Box 2)13. Indicators include pressure injuries, falls, urinary tract infections and staffing hours but not skin tear rates. However, skin tear rates should be included as a clinical indicator for any organisation providing services to older adults because of the frequency of these injuries, their impacts on individuals, and the many opportunities for preventing/minimising their occurrences.

Monitoring skin tear injury rates provides a valuable overview of service delivery, while auditing individual cases (tracer methodology) offers a window into systems and processes. The Ministry of Health14 suggests that examining the journey of a specific client/resident/patient facilitates understanding of the care that is being provided and shows if staff know how to deliver care, tests systems and processes and their function and validates the individual’s journey and outcomes (p.4).

A detailed review of just one service user’s experience with a skin tear injury can provide a range of valuable information, including:

- wound management practices and consistency with service policies – systems and processes for assessing/classifying/evaluating and reporting on wound progress; evidence-based wound management practices (e.g. not using skin closures on skin tears15); use of appropriate wound care products; monitoring for infection; checking that wounds are regularly monitored until they heal

- assessment and care planning – short-term plans related to the skin injury and its associated clinical requirements, such as analgesia, enhanced nutrition; strategies to minimise risk of skin injuries or further injuries, such as avoiding soaps and using skin moisturisers twice daily9, and the use of appropriate transfer equipment, for example, slider sheets

- capturing relevant data – initial and ongoing documentation in the clinical record related to the injury; completion of an accident/incident report; open disclosure to the individual and/or family; analysis of incident and accident data; mechanisms for responding to findings, reporting results to staff, actioning any identified deficits.

In conjunction with reviewing individual cases, an analysis of skin tear injury rates across the service can tell us about environmental factors that may contribute to these injuries, such as the times of day the injuries occur; the skin tear site; staff skill mix and ratios; staff education and knowledge deficits. These are modifiable factors the organisation can work towards addressing.

BOX 2: Indicators for safe aged care

An indicator is a measure or flag against which some aspect of a standard can be assessed. Indicators generally simplify and quantify complex phenomena and aid the communication of information about those phenomena. Indicators are information tools. They summarise data on complex issues to indicate the overall status and trends on those issues. Indicators are generally measures that link the processes of care with desirable outcomes13 (p.13-14).

Conclusion

Unfortunately, skin tears are a common occurrence for many older adults, resulting in pain, distress, and the potential for chronic wounds. Skin tear injuries result from many interlinked factors relating to the individual, the environment, and care practices. Some of these factors are modifiable, such as patient handling procedures, and others, such as significant frailty, are not.

While it is important that skin tears are prevented when possible, and when they occur are carefully and appropriately managed using best practice, these injuries also offer a picture into the quality of care received by individuals and a patient cohort. Rather than being a forgotten and inevitable wound for older adults, skin tears should be a key reminder of the complexity of care for this growing population.

View the PDF of this learning activity here >>

About the authors:

- Lesley Batten RN PhD is a senior researcher at Massey University, Palmerston North.

- Marian Bland RN PhD is a healthcare auditor.

This article has been peer reviewed by:

- Julie Betts RN MN, who is a wound care nurse practitioner at Waikato District Health Board.

- Rebecca Aburn RN MN, who is an infection prevention and control nurse specialist at Southern District Health Board with a special interest in wound care.

Recommended resources

- The International Skin Tears Advisory Panel website includes a range of resources, including the Skin Tear Resource Kit, a skin tear decision algorithm, and consensus statements relating to the prevention, prediction, assessment and treatment of skin tears. www.skintears.org

- The New Zealand Health and Safety Commission website includes comprehensive information on evaluating health quality.

www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-programmes/health-quality-evaluation - Pharmac’s 2015 Seminar Series focusing specifically on wounds is available via You Tube. The first part of the fourth video in this series, titled From skin tears to leg ulcers, covers a range of information relevant to skin tear prevention and management.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JKme8c9KyB4 - The Skin Safety Model proposed by Campbell, Coyer and Osborne offers a new perspective on older adults’ vulnerability to skin injuries and outlines a framework for skin care and the promotion of skin integrity. CAMPBELL J, COYER F & OSBORNE S (2016). The skin safety model: reconceptualising skin vulnerability in older patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 48(1) 14-22.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jnu.12176/full - Detailed information on the selection of wound products for skin tears can be found in the following article: LEBLANC K, BARANOSKI S & LANGEMO, D et al (2015) The art of dressing selection: a consensus statement on skin tears and best practice. Advances in Skin and Wound Care 29(1) 32-46.

- Information relating to the prevention of skin tears is outlined by: SUSSMAN G & GOLDING M (2011). Skin tears: should the emphasis be only their management?

Wound Practice and Research 19(2), 66-70.

References

- Personal anecdote as told to Marian Bland.

- LEBLANC K & BARANOSKI S (2014) Skin tears: the forgotten wound. Nursing Management 45(12) 36-46.

- CAMPBELL J, COYER F & OSBORNE S (2016) The skin safety model: reconceptualising skin vulnerability in older patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 48(1) 14-22. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jnu.12176/full

- INTERNATIONAL SKIN TEARS ADVISORY PANEL (2015). www.skintears.org

- SILVER CHAIN GROUP & CURTIN UNIVERSITY (2007) STAR skin tear classification system. Retrieved from www.woundsaustralia.com.au/publications/2010_wa_star-skin-tear-tool-g-04022010.pdf

- HOLLISTER AND INTERNATIONAL SKIN TEARS ADVISORY PANEL (2013). Skin tear resource kit. www.skintears.org/pdf/Skin-Tear-Resource-Kit.pdf

- MILNER E (2013). Simple tear but complex wound. Nursing Review 13, 18-19. www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/Falls/10-Topics/Milner-Nursing-Review-Nov-2013-Skin-tears.pdf

- ACC TREATMENT INJURY DATA FROM 1 JULY 2005. [Skin treatment injury data emailed by ACC to Nursing Review on 21 April 2017 following request for information.]

- CARVILLE K, LESLIE G, OSSEIRAN-MOISSON R, NEWALL N & LEWIN G (2014). The effectiveness of a twice-daily skin-moisturising regimen for reducing the incidence of skin tears. International Wound Journal 11, 445-53.

- STEPHEN-HAYNES J & CARVILLE K (2011). Skin tear made easy. Wounds International 2(4). Retrieved from www.woundsinternational.com/media/issues/515/files/content_10142.pdf

- MINISTRY OF HEALTH (2016a). Service standards. www.health.govt.nz/our-work/regulation-health-and-disability-system/certification-health-care-services/services-standards.

- HEALTH QUALITY AND SAFETY COMMISSION NEW ZEALAND (2016). Health Quality and Safety Indicators. www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-programmes/health-quality-evaluation/projects/health-quality-and-safety-indicators

- STANDARDS NEW ZEALAND AND MINISTRY OF HEALTH (2005) New Zealand Handbook – indicators for safe aged-care and dementia-care for consumers. SNZ HB 8163:2005.

- Ministry of Health (2014). Tracer methodology revisited. HealthCert Bulletin: Information for Designated Auditing Agencies 11, 4. www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/pages/healthcert-bulletin-11-april-2014.pdf

- LEBLANC K, BARANOSKI S & LANGEMO, D et al. (2015). The art of dressing selection: a consensus statement on skin tears and best practice. Advances in Skin and Wound Care 29(1) 32-46.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2012) Competencies for registered nurses. Retrieved January 2016 from www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Publications/Standards-and-guidelines-for-nurses

This learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council competencies 1.1, 2.8, 2.9.

Learning outcomes

- Understand rationale for developing a nursing portfolio.

- Know how to approach a self-assessment against the competencies using everyday practice examples.

- Increase familiarity with the Nursing Council of New Zealand website.

- Locate and review guidelines that underpin nursing practice.

Introduction

“What is a portfolio? Is it a PDRP? Is it a massive file of information about your practice? How do I even begin to self-assess when the competencies aren’t specific? Anyway, this will take weeks to put together…won’t it? I am good at my job, WHY are you auditing ME?”

This article looks at why nurses need to develop a portfolio and offers advice on how to effectively self-assess nursing practice against the Nursing Council of New Zealand competencies if faced by a recertification audit.

There are two circumstances when nurses need to present a portfolio:

Being randomly selected for a recertification audit of the continuous competence requirements by the Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ).

OR

Being employed by an organisation with an approved Professional Development and Recognition Programme (PDRP)8 and being required to submit a portfolio on a three-yearly cycle or wishing to apply for another level of practice. (Nurses on a PDRP should seek specific advice from their PDRP coordinator.)

Why portfolios?

The Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act (2003)¹ provides a framework for the regulation of health practitioners to protect the public where there is risk of harm from professional practice. The Act identifies responsible authorities (e.g. NCNZ) that have the role of ensuring all registered health practitioners, issued with an annual practising certificate (APC), are competent in their scope of practice.

The Council has the role of protecting the public by setting standards and ensuring that nurses are competent to practise under the Act. Each year the Council randomly selects five per cent of practising nurses for a recertification audit14.

Question: When you receive your APC notification from NCNZ, do you tick the boxes that declare:

- you have the required 450 practice hours (over three years)?

- you have the required 60 professional development hours (over three years)?

- you are competent to practice?

Answer: Yes? Then the NCNZ recertification audit is asking you to provide validated evidence for those ticks.

TIPS BOX 1

- ONLY include the requested items from the checklist.

- Filling a portfolio does not need to be a linear process. Start with the items you already have.

- Write about your everyday practice, in your own words.

- This isn’t about your best day ever, it’s about what you do every day.

What is a portfolio?

A portfolio is a standardised way of storing information that describes your competence to practice. It’s generally an A4 folder, or an electronic equivalent, with predefined sections making it easier to collate and audit.

Filling a portfolio for recertification

Content

The NCNZ provide a checklist14 on their recertification webpage. Only include the items requested, keep it simple. Three forms of verified evidence are required:

- Record of practice hours.

- Record of professional development hours.

- Assessment against the competencies

- Self-assessment

- Senior nurse or peer review

Check the NCNZ website for templates7, 14, 15 and information. If you cannot meet one or more of the requirements, contact the NCNZ to explain your situation and they will advise you what to do.

Verification

The evidence you provide in your portfolio must be verified, which means signed by someone who has either observed your practice or can confirm that the evidence you have provided is correct and that it is your work. This is often a manager or senior nurse. They must provide their name, designation and contact details.

Currency

A portfolio is about your current practice. All the evidence/practice examples you provide must be from the previous three years.

Privacy

Any inclusion of third party information without consent is a breach of privacy3, 17.

Assessment against the RN competencies

Which competencies?

The majority of New Zealand’s approximately 50,000 registered nurses (RNs) are in ‘direct-care’ clinical roles16 and will complete the RN clinical competencies. However, there are nurses working across health in myriad different roles who do not provide direct nursing care but still influence nursing practice and/or the nursing workforce. The Council has created competencies to recognise and accommodate the breadth of the scope and RNs must select a competency set that reflects their current practice. There are competencies for RNs in:

- clinical⁴ (the majority of RNs)

- management6/clinical management⁶

- education6, policy6, and research6.

This article looks at the clinical competencies⁴ in the four domains:

- Domain 1: Professional responsibility (five competencies)

- Domain 2: Management of nursing care (nine competencies)

- Domain 3: Interpersonal relationships (three competencies)

- Domain 4: Interprofessional healthcare and quality improvement (three competencies)

Nurses must provide ONE practice example for every competency. Each competency has ‘indicators’ listed – these are guides to help you select your example.

TIPS BOX 2

- Put your practice examples into the domains then start with the competency you think is the easiest to describe. The indicators may help you decide.

- Write a statement about your practice then support it with an objective example (an actual situation that occurred).

- See the examples provided for the RN clinical competencies.

The RN domains and competencies with general examples and tips to guide you

Domain 1: Professional responsibility

Competency 1.1 Accepts responsibility for ensuring that his/her nursing practice and conduct meet the standards of the professional, ethical and relevant legislated requirements.

This covers legislation, acts, ethics, codes, policies and standards that underpin practice. e.g. Privacy Act, the Code of Rights and workplace health and safety requirements. Refer to the NCNZ Code of Conduct5 and other guidelines.

EXAMPLE for Competency 1.1

Statement about your practice:

We had a refresher on the NCNZ Code of Conduct, social media guidelines and professional boundaries last year (see PD hours), which was great, and we keep copies in the office. I am very aware of the Privacy Act, the patient’s right to confidentiality and how that affects who I can talk to about the patient

Actual practice example:

Last month I was caring for a gentleman whose neighbour rang to ask for results of a recent blood test; she said she was helping to care for him and he had asked her to call. I explained that I could not discuss the patient’s condition or blood tests because… etc.

Competency 1.2 Demonstrates the ability to apply the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi to nursing practice.

This is specific to Māori, in relation to the Treaty. How do you partner in care? How do you protect or advocate? How do you facilitate patient/whānau participation?10

Competency 1.3 Demonstrates accountability for directing, monitoring and evaluating nursing care that is provided by enrolled nurses and others.

Delegation occurs up, down or sideways e.g. asking a colleague for help (sideways), escalating a difficult situation to a manager (up), directing a student, healthcare assistant (HCA), or a patient’s family or carers (down). Refer to the NCNZ Direction and Delegation Guidelines12, 9.

Competency 1.4 Promotes an environment that enables client safety, independence, quality of life, and health.

How do you promote a safe working environment? How do you anticipate and mitigate clinical risk? How do you promote patient wellbeing and safety e.g hazard identification, reporting incidents, infection control guidelines?

Competency 1.5 Practises nursing in a manner that the client determines as being culturally safe.

How do you care for patients who have different cultural¹⁴ requirements from your own? How do you ascertain their beliefs and how you do respond? How do you know if the patient determines your care is culturally safe? Think broadly and beyond ethnicity. Culture includes many things that are part of our everyday lives e.g. religion, disability, sexuality, beliefs, food, family culture and language.

Domain 2: Management of nursing care

Competency 2.1 Provides planned nursing care to achieve identified outcomes.

How do you plan care? Do you use nursing models of care? Consider how you plan for an acute episode or a chronic illness, long term or short term. Who do you involve in the planning?

Competency 2.2 Undertakes a comprehensive and accurate nursing assessment of clients in a variety of settings.

How do you conduct your assessments? Do you use an assessment framework e.g. SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan), mini-mental state examination, falls risk, InterRai? This could be initial assessment or assessment following a procedure, new medication or a regular reassessment. Consider how often you assess; you may have noticed something using your observation skills that prompted you to undertake a more focused assessment.

EXAMPLE for Competency 2.2

Statement about your practice:

We see walk-in patients and also take phone calls from patients. We need to be able to quickly assess in a variety of ways.

Actual practice example:

Walk-in: Last week a new patient presented with chest pain. As he came through the door I saw he was pale and sweaty, rubbing his chest. I immediately used the OLD CARTS chest pain assessment tool … etc.

Phone call: A young mum rang about her child who had a fever of 38.8 and had been unwell overnight with an ‘odd’ cough’. I used the Traffic Light System to identify the immediate risks: I asked for the child’s colour, activity … etc.

Competency 2.3 Ensures documentation is accurate and maintains confidentiality of information.

How do you maintain clear, concise, organised and current documentation?

EXAMPLE for Competency 2.3

Statement about your practice:

I document as soon as possible after a patient interaction; I always write things down in accurate detail as soon as I can with a time, date and signature, and then print my name.

Actual practice example:

About eight months ago a visitor made a complaint, claiming I gave their elderly relative the wrong advice about a medication. My manager checked back into the patient’s notes and I had written the conversation down in detail, timed and dated it, with a note that I had confirmed everything with the patient … etc.

Competency 2.4 Ensures the client has adequate explanation of the effects, consequences and alternatives of proposed treatment options.

How do you describe and explain a treatment, medication or a procedure to the patient? Do you encourage questions? Do they need a support person/interpreter/family member? Do you describe the alternatives and possible outcomes? Do you use printed information?

Competency 2.5 Acts appropriately to protect oneself and others when faced with unexpected client responses, confrontation, personal threat or other crisis situations.

What systems does your workplace have for crisis situations and what is your role in managing these? For example, cardiac arrest, security threat, anaphylaxis and other significant events.

Competency 2.6 Evaluates client’s progress toward expected outcomes in partnership with clients.

How do you assess if your care is safe and effective? How have you involved patients in care planning? How do you contribute to discussions and planning for the patients?

EXAMPLE for Competency 2.6

Statement about your practice:

I regularly meet with patients (and, if appropriate, their families) to discuss their requirements and preferences for their care.

Actual practice example:

I care for an elderly gentleman who is now unable to attend appointments for wound care because of chronic pain, transport issues and living alone. I recently organised to meet with him to review the options for his situation so he could get the care he needed in a way which met his planned care needs and his preferences starting with… etc.

Competency 2.7 Provides health education appropriate to the needs of the client within a nursing framework.

Why is health education important and how do you ensure you are offering it in a timely, consistent and appropriate way? Do you use printed resources or websites? Is it age and ability appropriate e.g. quit smoking, green prescription or a new medication? It could be to a patient, family or caregivers. How do you evaluate the effectiveness of your education?

Competency 2.8 Reflects upon, and evaluates with peers and experienced nurses, the effectiveness of nursing care.

How do you support your colleagues and peers to reflect on their practice? Does your employer have a system for seeking advice or debriefing? Have you made changes to patient care following reflection or professional discussion? Do you attend professional supervision?

Competency 2.9 Maintains professional development (PD).

You should include your PD record, but you can always add a reflection on a specific PD activity and how it affected your practice.

Domain 3: Interpersonal relationships

Competency 3.1 Establishes, maintains and concludes therapeutic interpersonal relationships with client.

It’s all about communication. How do you approach people every day; new patients or patients you have known for a long time? How do you form trusting relationships quickly and how do you maintain your longer term professional relationship with patients? How do you demonstrate knowledge of verbal and nonverbal skills (body language) in your communication with patients?

Competency 3.2 Practises nursing in a negotiated partnership with the client where and when possible.

Consider the patient’s right to refuse treatment – do you practice informed consent? How will the planned care work for the patient e.g. can they get to an appointment? What do you discuss with the patient to get the care they need in the right way, at the right time and place?

Competency 3.3 Communicates effectively with clients and members of the health care team.

Consider the many techniques you use to communicate with patients and to the team. How do you know they are effective?

EXAMPLE for Competency 3.3

Statement about your practice:

I think communication and listening is key to good practice. I always assess carefully when I meet patients to find out how they need to communicate and what works best for them.

Actual practice example:

Recently a new resident, an elderly gentleman who is profoundly deaf, had staff shouting instructions to him. I felt this undermined his dignity and was ineffective. I introduced myself to him and asked if I could sit next to him. I asked him if I could use a pen and paper to get my messages across in writing which he really liked … etc.

Domain 4: Interprofessional healthcare and quality improvement

Competency 4.1 Collaborates and participates with colleagues and members of the healthcare team to facilitate and coordinate care.

This is about the wider team, sometimes outside your own organisation. How do you work with other providers? How do you approach handover, multi-disciplinary meetings or case reviews? How do you organise a referral e.g. to a dietician or podiatrist, or discuss and plan care with other members of the healthcare team?

Competency 4.2 Recognises and values the roles and skills of all members of the healthcare team in the delivery of care.

Do you recognise when different skills are needed e.g. a physiotherapist, a social worker, a doctor? How do roles and clinical skills differ? How do you recognise and coordinate this e.g. in a discharge plan, patient deterioration, coordination of a procedure or appointment?

Competency 4.3 Participates in quality improvement activities to monitor and improve standards of nursing.

This could be participation in a clinical audit, survey, or nursing care quality initiative e.g. procedure technique, wound dressing, medication administration, documentation or communication process. Hazards, unsafe equipment or incident reporting. Focus on nursing practice.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a portfolio does not need to be confusing. Just step back, reflect on your practice and start recording your examples, competency by competency.

About the author:

- Liz Manning, RN, BN, MPhil (Nursing), FCNA(NZ) is a director of Kynance Consulting and is a nurse consultant who has worked in the area of portfolios, assessment, auditing and PDRP for many years.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- Linda Adams RN PG Cert HSc is a quality advisor for MedScreen. She is a former PDRP nurse advisor, recertification and PDRP auditor and competence assessor for NCNZ.

- Lorraine Hetaraka-Stevens RN PG Dip (nursing), MNurs (in progress) is an experienced competence assessor and nurse leader who is currently nurse leader of the National Hauora Coalition.

View PDF of this learning activity here >

REFERENCES

- HEALTH PRACTITIONERS COMPETENCE ASSURANCE ACT (2003). Retrieved December 2016 from www.legislation.govt.nz.

- MANNING L (2015). Tips for a top nurse portfolio. Nursing Review 15(2) 28.

- NEW ZEALAND NURSES ORGANISATION (2016). Guideline: Privacy, Confidentiality and Consent in the Use of Exemplars of Practice, Case Studies, and Journaling, 2016.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2007). Competencies for Registered Nurses. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2012). Code of Conduct. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2011). Competence Assessment Form for Registered Nurses in Clinical Management. Competence Assessment Form for Registered Nurses Practising in Education. Competence Assessment Form for Registered Nurses Practising in Management. Competence Assessment Form for Registered Nurses Practising in Policy. Competence Assessment Form for Registered Nurses Practising in Research.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2014). Examples for self-assessment and senior nurse assessment for the registered nurse scope of practice.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2013). Framework for the approval of professional development and recognition programmes to meet the continuing competence requirements for nurses. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2011). Guideline: Direction and Delegation of Care by a Registered Nurse to a Health Care Assistant.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2011). Guidelines for Cultural Safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori Health in Nursing Education and Practice. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2012). Guidelines: Professional Boundaries. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2011). Guideline: Responsibilities for Direction and Delegation of Care to Enrolled Nurses.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2012). Guidelines: Social Media and Electronic Communication. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND Recertification Audits & Recertification Audit Checklist.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2011). Template for Evidence of Professional Development Hours.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2015). The New Zealand Nursing Workforce: A Profile of Nurse Practitioners, Registered Nurses and Enrolled Nurses 2014–15. Wellington: Author.

- PRIVACY ACT (1993). Retrieved December 2016 from www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1993/0028/latest/DLM296639.html.

This learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council competencies 1.1, 1.4, 2.1, 2.8, 2.9, 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3.

Learning outcomes

- Recognise the signs and symptoms of phlebitis.

- Summarise the distinguishing features of the four types of phlebitis.

- Take appropriate action to reduce the risks of phlebitis.

- Identify the risk factors and potential causes for IV cannula complications.

- Reflect on improvements that can be made to nursing practice to reduce IV complications.

Introduction

“Sam” (64) was admitted for elective surgery on his shoulder. He had had a few PIVCs during his admission. Medication from one of these cannulae (in his forearm), had infiltrated the surrounding tissue and the tissue then became necrotic. He required grafts and further surgery. This became infected. The infection went to his shoulder and he required further washouts of his shoulder1.

Insertion of a PIVC is one of the most common invasive clinical procedures performed in hospitals globally2 yet nurses are still not observing, assessing nor documenting the state of these regularly enough to reduce the risk of complications to the patient. PIVCs provide direct access into the venous system. Nurses must ensure that their knowledge and skills are up to date and based on current evidence-based practice to reduce the risk of patients with PIVCs preventing complications3.

Phlebitis

Phlebitis is one of the main complications from PIVC, with research indicating that the incidence can vary widely from less than 3 per cent up to more than 65 per cent depending on the clinical setting. This broad range suggests poor identification of phlebitis or poor reporting protocols4.

Phlebitis is defined as inflammation of the tunica intima or inner layer (see Fig. 1) of the vein, characterised by pain, redness and swelling5. The area may feel warm with a cord-like appearance of the vein and the patient may feel pain or discomfort when medication is administered.

There are four main types of phlebitis.

Chemical phlebitis is caused by fluid or medication being infused through the cannula. Key factors such as pH and osmolarity (the concentration of a solution) are known to have an effect on the incidence of phlebitis6. Blood has a pH of 7.35-7.45. Medications outside this range have the potential to damage the tunica intima (Fig. 1), the delicate inner layer of the vein (see Fig. 1), increasing the risk of patients developing phlebitis. This increases the risk of further injury to the vein, such as sclerosis, infiltration or thrombosis7.

Mechanical phlebitis happens when there is movement of the PIVC within the vein causing inflammation. This can be due to unskilled insertion or with placement of the cannula near a joint or venous valve, poorly secured cannulae, and manipulation of the cannula during administration of medication or fluid8. Having an insecure PIVC increases the risk of mechanical and infective phlebitis, with movement of the cannula causing migration of bacteria into the vein9.

Infective phlebitis is caused by bacteria entering the vein. Inflammation of the vein may begin as a non-infectious process caused by manipulation of the cannula or irritation from an infusion. Both chemical and mechanical phlebitis can produce inflammatory debris, which may serve as a culture medium for micro-organisms to multiply10. Once bacteria come into contact with the PIVC, they secrete a glue-like substance that causes the bacteria to stick to the plastic. This slimy protective substance is called biofilm. Antibiotics and white blood cells can’t penetrate this layer to kill the bacteria. Flushing and infusions can cause the biofilm to break off and travel into the patient’s bloodstream, with the associated risk of bacteraemia11.

Post-infusion phlebitis is an inflammatory response occurring after a PIVC has been removed. While most low-grade phlebitis will resolve when the cannula is removed, phlebitis may occur up to 48 hours later, with some evidence of occurrence up to 96 hours later8.

The Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice12 published in 2016 by the Infusion Nurses Society (INS), highly recommends the use of a phlebitis scale that is valid, reliable and clinically feasible; for example, the Jackson VIP Scale (Fig. 2). Intravenous Nursing New Zealand13, supports the use of the Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice to promote a consistent approach to catheter management when monitoring phlebitis. Interestingly, a systematic literature review published in 201414 identified more than 70 different phlebitis assessment scales in use worldwide. Nurses still need to be aware of the treatment required for the different types of phlebitis.

Management of phlebitis

Nurses should determine the possible aetiology of the phlebitis as noted below; apply a warm compress; elevate the limb; provide pain relief as needed; consider other pharmacologic interventions, such as anti-inflammatory agents; and use a visual scale, like the Jackson VIP Scale (Fig. 2), to consider whether removal (resiting) of the cannula is necessary10, 11. For example, if two of the following three are evident: pain near the IV site, erythema or swelling, no matter what the aetiology of the phlebitis, the PIVC must be removed and resited.

Chemical phlebitis: evaluate the infusion therapy and need for different IV access (e.g. central venous access device), different medication, or a slower rate of infusion; determine if removal of the PIVC is needed. Provide interventions as above10, 11.

Mechanical phlebitis: stabilise the IV cannula, apply heat, elevate the limb, and monitor closely. If signs and symptoms persist after 48 hours, consider removing PIVC as per Jackson VIP Scale (Fig. 2)10, 11.

Infective phlebitis: if suspected, (pain, erythema, swelling), remove the PIVC. Follow local policy regarding microbiology culture to identify the organism and incident reporting. Medical assessment will be required for the initiation of any antibiotic treatment. Monitor for signs of systemic infection10, 11.

Post-infusion phlebitis: if this appears to be a bacterial source, ensure that medical review is initiated, monitor for signs of systemic infection; if nonbacterial, apply warm compress, elevate limb, provide analgesics as needed, and consider other pharmacologic interventions. such as anti-inflammatory agents or corticosteroids as necessary10, 11.

Reducing the risks of phlebitis

Having a skilled practitioner or IV team inserting IV cannulae is proven to reduce many complications of PIVC15. IV teams are not always practical for all settings, but having skilled, trained IV practitioners who regularly update their skills and knowledge is a necessity for improving clinical quality and reducing risk. It has been demonstrated that skilled cannulators have a significantly higher first-time insertion rate, which is associated with a lower incidence of phlebitis and failure16.

Chemical phlebitis

- patients at risk may need to be referred for a central venous access device, such as a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) depending on the pH and tonicity of the medications to be administered7.

Mechanical phlebitis

- Prevent movement by carefully securing the cannula with a sterile, occlusive, transparent semipermeable polyurethane dressing9.

- Ensure the cannula hub is not directly accessed close to the insertion site9.

- Keep dressing dry and redress if the dressing loses its integrity.

- Select the smallest practical cannula for the largest possible vein.

- Avoid placing PIVCs near to joints i.e.

- ante-cubital fossa, to reduce irritation of the vessel wall by the tip of the cannula during movement6.

Infective phlebitis

As above (mechanical phlebitis), plus:

- Strict hand hygiene.

- Clipping excess hair from the preferred insertion site.

- Ensure strict aseptic non-touch technique during insertion of the cannula.

- Perform skin antisepsis with >0.5 per cent Chlorhexidine/70 per cent alcohol12, cleansing the skin with friction for 30 seconds and allow the solution to dry naturally. If a Chlorhexidine/alcohol solution is contraindicated, consider using povidone-iodine or 70 per cent alcohol wipes.

- No repalpating of the preferred site after cleansing.

- Use appropriate sterile IV dressing.

- ‘Scrub the hub’ of the needleless connector every time the cannula is accessed with single use disinfecting agent e.g. 70 per cent alcohol wipes or >0.5 per cent Chlorhexidine/70 per cent alcohol wipe, for at least 15 seconds12.

- Check the integrity of the PIVC dressing.

- Carefully remove the dressing that has lost its integrity and replace with new sterile dressing, taking care not to manipulate the sited cannula.

- Only use flush solutions from a single use system. Minimum of 10mL pre- and post-IV medication or according to local medication policy11.

Post-infusion phlebitis

A recent Australian study17 noted that the main predictor of post-infusion phlebitis was cannulae inserted under emergency situations, reinforcing the following recommendations:

- Replace all PIVC inserted under emergency conditions as soon as feasibly possible, i.e. within 24 to 48 hours12.

- Observe the insertion site for at least 48 hours after removal of the cannula.

- Educate the patient or family on discharge about signs and symptoms of phlebitis17.

Reducing the risk of other PIVC complications

Nurses also need to be cognisant of other complications leading to PIVC failure.

A quarter of PIVCs fail through accidental dislodgement or occlusion. Infiltration and extravasation (see Definitions box), haematoma formation or thrombophlebitis and septic thrombophlebitis may then occur18. It has been suggested that the use of visualisation devices (infrared or ultrasound) can increase the success of first-attempt insertion and decrease trauma to the patient19.

Good PIVC management

Early identification and intervention are critical to prevent serious adverse events, such as extensive tissue injury or nerve injury leading to compartment syndrome requiring surgical intervention20.

If a patient reports any burning or stinging at or around the insertion site or anywhere along the venous pathway:

- stop infusion immediately

- disconnect the IV tubing from the PIVC

- attempt aspiration of the residual medication from the cannula

- remove the cannula

- notify the medical team or senior nurse as further intervention may be required depending on the factors related to the injury13.

Elevation of the affected limb for up to 48 hours may help with reabsorption of the infiltrate. Local thermal treatment depends on the pharmacological agent infused and expert advice should be sought as to whether heat or cold is appropriate20.

If an extravasation injury does occur, ensure that the appropriate documentation is completed using an approved extravasation scale and following local policy for reporting13.

Correct PIVC placement and observation

Key factors to a successful infusion include ensuring correct placement and stabilisation of the cannula (with the patient reporting no pain or burning), and no swelling around the insertion site. The recommended guides should be carefully adhered to during infusion of any medication or fluid to reduce the risk of tissue injury and loss of the PIVC. The cannula insertion site should also be assessed and observed at least every four hours20.

Placement of PIVCs is recommended in forearm veins as opposed to the hand, wrist or ante-cubital fossa as the forearm sites are less prone to occlusion, accidental dislodgment and phlebitis21. Nurses are well placed to advocate for their patient to have a central venous access device (CVAD) placed for the administration of vesicant medications18.

Flushing protocols and administration of IV medications

There is very little research and a high degree of practice variation in the maintenance of PIVC, including the role of flushing to prevent complications. It is highly recommended that nurses refer to the manufacturer’s guidelines and local organisational policy for the recommended preparation and speed of infusion in order to prevent vein injury21. For example: 1.2g Amoxicillin plus Clavulanic Acid (Augmentin). Administration notes: Inject slowly over three to four minutes22.

Good documentation

Documentation is essential for accountability, as well as the maintenance of a high standard of professional practice; however, it is often overlooked, especially when the workload is high21.

The use of a pre-printed care plan can be useful. An example used in one New Zealand hospital includes documentation of:

- Patient information and consent

- date and time of insertion

- name and signature of cannulator

- location, type and gauge of cannula

- indication for use.

- Ongoing care documentation should include:

- cannula checked & cannula required

- needleless access device insitu

- dressing intact & dated

- cannula flushed (flush solution)

- VIP score & indication for use

- cannula removed – including date, time and reason12,13,21.

Conclusion

Early recognition of IV complications through regular assessment and observation enables appropriate and timely intervention, minimising disruption to the patient’s treatment, improving patient outcomes, as well as reducing healthcare costs involved in extra treatment and procedural requirements and increased bed days from unnecessary complications.

The following quote reinforces the intent of this article:

“Penetration of a patient’s natural protective skin barrier with a foreign body that directly connects the outside world to the bloodstream for a prolonged period of time is not to be taken lightly. Insertion of an IV catheter is an invasive procedure that introduces multiple risks and potential morbidities, and even mortalities, and should be given the respect that it deserves.”23

View PDF of this article (and related learning activity) here >>

Recommended Resources

AVATAR is an Australian-based teaching and research group aimed at “making vascular access complications history”: http://www.avatargroup.org.au

Intravenous Nursing New Zealand (IVNNZ Inc.) is a voluntary, non-profit, professional development organisation and affiliated international member of the Infusion Nurses Society (INS) and is dedicated to Best Practice Recommendations and Standards of Practice for Infusion Therapy: http://www.ivnnz.co.nz/

Infusion Nurses Society (2016.) Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice Journal of Infusion Nursing. 39 (1S)

About the author:

Bev Hopper MHPrac (Nursing), PG Cert Advanced Nursing Practice (Orthopaedics), BHSc (Nursing), NZRN (Comp) is the Clinical Nurse Specialist (Out Patient IV Antibiotics) at Waitemata District Health Board in Auckland.

This article was peer reviewed by:

Catharine O’Hara RN MN is Clinical Nurse Specialist (Lead) Intravenous & Related Therapy at MidCentral District Health Board’s Department of Anaesthesia & ICU

Rachael Haldane, RN BN PGDip HSc is a clinical nurse specialist, infusion services for Nurse Maude, Christchurch.

REFERENCES

- Personal anecdote of Beverley Hopper.

- AHLQVIST M, BERGLUND B, NORDSTROM G, KLANG B ET AL. (2010).

A new reliable tool (PVC assess) for assessment of peripheral venous catheters. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 16 (6), 1108-15. - NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2007). Competencies for Registered Nurses. Retrieved September 2016 from www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Publications/Standards-and-guidelines-for-nurses.

- OLIVEIRA A & PARREIRA P (2010). Nursing interventions and peripheral venous catheter-related phlebitis. Systematic literature review. Referência: Scientific Journal of the Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing 3(2), 137-47.

- DOUGHERTY L (2008). Peripheral Cannulation. Nursing Standard 22 (52), 49-56.

- HIGGINSON R (2011). Phlebitis: treatment, care and prevention. Nursing Times 107 (36), 18-21.

- KOKOTIS K (2015). Preventing chemical phlebitis. Nursing 28 (11), 41-7.

- MACKLIN D (2003).Phlebitis: A painful complication of peripheral IV catheterization that may be prevented. The American Journal of Nursing 103(2), 55-60.

- HIGGINSON R (2015). IV cannula securement: protecting the patient from infection British Journal of Nursing (8)24, S23-S28.

- MALACH T, JERASSY Z, RUDENSKY B, SCHESINGER Y ET AL. (2006). Prospective surveillance of phlebitis associated with peripheral intravenous catheters. American Journal of Infection Control 34 (5), 308-12.

- RYDER M (2005). Catheter related infections: It’s all about the bio-film. Topics in Advanced Practice Nursing eJournal 5 (3).

- INFUSION THERAPY STANDARDS OF PRACTICE (2016). Retrieved September 2016 from www.anzctr.org.au/AnzctrAttachments/369954-INSper cent20Standardspercent20ofper cent20Practice 2016.pdf

- INTRAVENOUS NURSING NEW ZEALAND. (2012). Retrieved September 2016 www.ivnnz.co.nz/files/file/7672/IVNNZ_Inc_Provisional_Infusion_Therapy_Standards_of_Practice_March_2012.pdf.

- RAY-BARRUEL G, POLIT D, MURFIELD J & RICKARD C (2014). Infusion phlebitis assessment measures: a systematic review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 20 (2), 191-202.

- WALLIS M, MCGRAIL M, WEBSTER J, MARSH N et al (2014). Risk factors for peripheral intravenous catheter failure: a multivariate analysis of data from a randomised control trial. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 35 (1), 63-8.

- DA SILVA G, PRIEBE S, DIAS F (2010). Benefits of establishing an intravenous team and the standardisation of peripheral intravenous catheters. Journal of Infusion Nursing 33 (3), 156-60.

- WEBSTER J, MCGRAIL M, MARSH N, WALLIS M ET AL (2015). Post-infusion phlebitis: incidence and risk factors. Nursing Research and Practice, 2015.

- SIMONOV M, PITTIRUTI M, RICKARD C, CHOPRA V (2015). Navigating venous access: A guide for hospitalists. Journal of Hospital Medicine 10 (7), 471-8.

- SALGUIRO-OLIVEIRA A, PARREIRA P, VEIGA P (2012). Incidence of phlebitis in patients with peripheral intravenous catheters: the influence of some risk factors. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 30 (2), 32-9.

- DOELLMAN D, HADAWAY L, BOWE-GEDDES L A, FRANKLIN M, ET AL. (2009). Infiltration and extravasation: Update on prevention and management. Journal of Infusion Nursing 32 (4), 203-11.

- BROOKS N (2016). Intravenous cannula site management. Nursing Standard 30, 53-62.

- New Zealand Hospital Pharmacists Association (2015). Notes on injectable drugs (7th ed.) Wellington, New Zealand.

- HELM R, KLAUSNER J, KLEMPERER J, FLINT L, ET AL (2015). Accepted but unacceptable: Peripheral IV catheter failure. Journal of Infusion Nursing 38 (3), 189-203.

This learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council competencies 1.1, 1.4, 2.1, 2.8, 2.9, 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3.

Learning outcomes

- define catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI)

- describe the pathogenesis of CAUTI

- identify risk-factors associated with CAUTI

- identify CAUTI prevention strategies that nurses can implement to promote patient safety.

Introduction

Introduction

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is the most common healthcare-associated infection (HAI) worldwide1. Urinary tract infections (UTI) comprise 40 per cent of HAIs and 80 per cent of these UTIs are attributed to indwelling catheters2. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection complications include genito-urinary tract infections and life-threatening bloodstream infections that develop secondary to a UTI4.

The primary risk factor for CAUTI is the prolonged use of urinary catheters5. With the catheter in place, the daily risk for bacterial growth in the urine or bacteriuria is about 3 to 7 per cent6,7. Ten per cent of patients with bacteriuria will develop CAUTI, while three per cent will go on to develop bloodstream infections. Bloodstream infections result in discomfort, prolonged hospital stays, increased costs and, sometimes, deaths3,4,8.

CAUTI events are costly for both the patient and the entire healthcare system7,9. The clinical consequences and economic burden of CAUTI makes CAUTI prevention fundamental to patient safety. (See Box 1 below for definition of CAUTI)

CAUTI pathogenesis

Indwelling urinary catheters are used therapeutically to drain urine from the bladder; however, when used inappropriately, catheters can pose both mechanical and physiological risks to patients1.

Catheters cause mechanical erosion of the bladder mucosa and ischemic damage when swelling occurs due to blockage. Catheters also provide a route for microbial entry from the colonised perineum to the sterile bladder through a catheter’s internal and external surfaces1. Microorganisms that colonise the perineum and intestinal tract cause about two-thirds of CAUTI, while a third are caused by urine collection systems contaminated by healthcare workers’ hands11.

Urinary catheters interrupt the normal bladder defence mechanism1,11. When bacteria are present in the urinary system, the bacteria bind to the sterile mucosa, which starts an inflammatory response characterised by the inflow of neutrophils and shedding of epithelial cells12. When the catheter is in place, the bacteria bind to catheter surfaces and form a biofilm, which bypasses the normal bladder defence mechanism11.

Biofilm

Biofilm formation is central in the development of CAUTI12. Biofilms are slimy structures made up of communities of microorganisms. Biofilm forms when a conditioning film of host components attaches itself to the inner and outer surface of a urinary catheter after insertion. Biofilm traps free-swimming microorganisms that then multiply, attract more microorganisms, and further secrete extracellular matrix that makes the biofilm grow in size. Biofilm microorganisms function as a community and communicate closely with one another1,13. Some microorganisms also detach from the biofilm and seed the urine1.

Biofilms help microorganisms survive through: resistance to being swept away by shear forces; resistance to being engulfed by other cells, and resistance to antimicrobial agents1,13. Studies have shown that antimicrobial agents penetrate biofilms; however, the slow growth of microorganisms in a biofilm confers antimicrobial resistance11. The affinity of microorganisms with each other in a biofilm also permits the exchange of antimicrobial resistance genes, thereby increasing the risk for other CAUTI complications12.

Risk factors for CAUTI

Prolonged catheterisation is the major risk factor for CAUTI3,5. Other risk factors include: non-adherence to aseptic technique during catheter insertion11; poor hand hygiene compliance8; catheter insertion after the sixth day of hospitalisation; poor hand hygiene; catheter insertion outside the operating room9, and a break in the closed drainage system8,14.

Strategies to prevent CAUTI

Multiple strategies have been shown to prevent CAUTI. Prevention strategies were published by the US CDC in 1981 and subsequently updated in 20098 and 20143. These strategies and recommendations were summarised by the USA-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)7 into four components of urinary catheter care. Australia and New Zealand’s 2013 catheterisation guidelines break down the principles for reducing CAUTI into similar sections or components, but with the addition of a section on selecting the appropriate catheter type and drainage system18. The following discussion expands on those components of care to include other evidence-based recommendations.

Component One: Reduce inappropriate use of urinary catheters

Urinary catheter presence in the bladder is the primary risk for CAUTI; thus, reducing inappropriate use is the best way to prevent it11,15.

Catheters should only be inserted when clinically indicated.

Some indications for using short-term catheterisation are:

- acute and chronic urinary retention

- urinary obstruction

- close monitoring of fluid intake and output of critically ill patients

- risk of worsening sacral decubitus ulcer due to urinary incontinence or end-of life care5,8,16,17

- selected surgical procedures that last more than three hours

- management of acute urologic conditions when straight catheterisation is not possible8,16,17

- patients undergoing urologic surgery or surgery on other genitourinary tract structures

- patients anticipated to receive large-volume infusions or diuretics during surgery, and the need for intraoperative monitoring of urinary output.

- urinary catheterisation may also be indicated for patients requiring prolonged immobilisation8.

Inappropriate indications for using indwelling catheters include:

- as a substitute for nursing care of incontinent patients

- as a means of obtaining urine for culture when the patient can voluntarily void8

- for prolonged postoperative duration without appropriate indications8.

Nurses are also encouraged to: use a bladder scanner in assessing urine volume to reduce unnecessary catheter insertions, and consider other bladder management methods such as intermittent catheterisation3,8.

Component Two: Perform proper techniques for indwelling catheter insertion

Indwelling catheter insertion is an invasive procedure that requires care and proper technique to avoid pain, trauma and infection. For more guidance you can view the best-practice urinary catheterisation guidelines [see recommended resources] developed by the Australia and New Zealand Urological Nurses Society (ANZUNS)18.

Selection of catheter

- Select appropriate length and type of catheter for patient.

- Use smallest gauge catheter possible, while ensuring good drainage to minimise bladder neck and urethral trauma3,8.

Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene before and after catheter insertion prevents the introduction of microorganisms into the catheter, thereby minimising CAUTI risk3,8.

Aseptic technique and the use of sterile equipment

Aseptic technique minimises the risk of microbial entry into the sterile urinary system. Aseptic technique during catheter insertion, the use of sterile equipment, and even the setting of catheter insertion all play a significant role in reducing the incidence of bacteriuria19. The use of sterile gloves, drape, sponges, an appropriate antiseptic or sterile solution for periurethral cleaning, and a single-use packet of lubricant jelly for insertion is recommended8.

Secure indwelling catheters after insertion to prevent movement and urethral traction

Indwelling catheters should be kept secure to minimise movement that may cause urethral trauma or erosion of the bladder mucosa7,8,20. Trauma to the bladder mucosa releases organic molecules, which, when combined with glycoprotein from the urine, facilitate bacterial colonisation, thereby increasing CAUTI risk12.

Component Three: Implement proper urinary catheter maintenance procedures

Proper maintenance of urinary catheters focuses on maintaining a closed system and maintaining an unobstructed urine flow8. Ongoing good hand and general hygiene is also very important3,8.

Maintain a closed drainage system

Urinary drainage systems should remain closed because disconnections at the catheter-collecting tube junctions have been shown to significantly increase bacteriuria risk due to bacterial spread along the internal surface of the catheter.

The relative risk of acquiring CAUTI the day after catheter disconnection has been shown to double21. If there are breaks in aseptic technique, disconnection or leakage, nurses should replace the catheter and collection bag using aseptic technique and sterile equipment8.

Microbial spread along the internal catheter surface can also happen if urine in the collection bag is contaminated through improper emptying. In this way microorganisms can gain access to the drainage system and ascend to the bladder, particularly if standard precautions are not observed22. When draining the bag, nurses are also encouraged to avoid splashing urine, to use a separate clean collecting container for each patient, and to prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the non-sterile collecting container3,8,20.

The CDC further recommends that the collection of urine samples should be performed aseptically through the needleless sampling port or the drainage bag using a sterile syringe/cannula after the port is cleansed with a disinfectant8.

Maintain an unobstructed urine flow

Unobstructed urine flow can be achieved through the following measures: keeping the catheter and collection bag free from coils or kinks and off the floor at all times, and emptying the collection bag regularly3,8,20,23.

A study conducted among intensive care patients showed that drainage tubing kinking or coiling was significantly associated with fever and bacteria in the urine23. The presence of kinks and coils is thought to compromise bladder emptying and possibly increase bladder hydrostatic pressure, thereby causing transient bacteriuria, thus the fevers.

The recommendation that the collection tubing and bag should always remain below the patient’s bladder to allow proper urine drainage is supported by a large prospective study in the US showing that improper positioning of the collection tubing and bag is associated with a significantly increased risk in CAUTI because of the backflow of potentially contaminated urine from the drainage bag24.

The authors of a European microbiology study explain that when the drainage bag is placed above the level of the bladder, microorganisms from the urine bag can gain access to the drainage system along the internal catheter surface and ascend to the bladder22.

Component Four: Review catheter necessity daily and remove promptly

The length of time a urinary catheter is in place is the strongest predictor of CAUTI development8. Recommendations indicate that indwelling urinary catheters should be removed as soon as possible post-operatively, preferably within 24 hours unless there are indications for continued use8. It has been found that patients develop bacteriuria at a rate of three to seven per cent per day7. This risk increases to 25 per cent when the catheter remains in place for one week and increases to nearly 100 per cent when the catheter remains in place for up to a month7.

Effective catheter care involves collaborative effort8; however, nurses remain largely responsible for indwelling catheter care. Daily assessment of catheter need and the possibility of removal is recommended3, with electronic alerts or other daily reminder systems important in acute care. Nurses are also advised to use standard precautions during catheter removal to prevent cross-transmission of microorganisms, thereby preventing CAUTI8.

Conclusion

In summary, the components of care to prevent CAUTI include: reduction of inappropriate use of urinary catheters; performance of proper indwelling catheter insertion techniques; selection of correct catheter and drainage system; implementation of proper catheter maintenance procedures, and removal of catheters in a timely manner.

These catheter management components are all inter-related and can help to prevent this most common of the healthcare-associated infections – CAUTI.

In addition, education on CAUTI prevention should not only focus on one aspect of care, but should also be spread across all components

of care.

Box 1: CAUTI definition

The definition of CAUTI varies worldwide, as does the criteria for identifying CAUTI. One of the more commonly used definitions in acute care settings is that of the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) of the United States Government’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The NHSN define CAUTI as a urinary tract infection in a person with an indwelling urinary catheter for more than two days and at least one of the following criteria:

- With catheter still in place, the person develops at least one of the following – fever (> 38C), suprapubic tenderness, costovertebral angle pain, and a positive urine culture of > 105 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml with no more than two species of microorganisms.

- With catheter removed the day prior to, or on the day, the person manifests at least one of the following – fever (> 38C), urgency, frequency, dysuria, suprapubic tenderness, costovertebral angle pain, and a positive urine culture of > 105 CFU/ml with no more than two species of microorganisms (reference 10).

View the PDF of this article (and related learning activity) here >>

Recommended resources:

Detailed best-practice urinary catheterisation guidelines from the Australia and New Zealand Urological nurses Society (ANZUNS) can be downloaded from their website at www.anzuns.org

Evidence-based guidance on the prevention of healthcare-associated infections in primary and community care can be found at the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) website at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg139/evidence

The CDC website also offers resources for both patients and healthcare workers. The CDC guideline for CAUTI prevention is downloadable from their website at https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/cauti/index.html

About the authors:

- Monina Gesmundo RN, BSN, PGCertTT, PGDipHSc, MNur (Hons) until recently worked as a clinical nurse specialist for infection prevention and control at Counties Manukau Health. She is currently a lecturer at the School of Nursing, Massey University.

- Dr Anna King is a lecturer at the School of Nursing, the University of Auckland.

Lisa Stewart, RN, BA, PGDipHSc, MNur (Hons) is a professional teaching fellow and PhD candidate at the School of Nursing, the University of Auckland.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- Ruth Barratt RN BSc MAdvPrac (Hons), a clinical nurse specialist infection prevention and control for the Canterbury District Health Board.

REFERENCES

- SIDDIQ D & DAROUICHE R (2012). New strategies to prevent catheter-urinary tract infections. Nature Reviews Urology, 9, 305-314.

- WEBER D, SICKBERT-BENNETT E, GOULD C ET AL. (2011). Incidence of catheter-associated and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infections in a healthcare system. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 32(8), 822-823.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/661107 - LO E, NICOLLE L, COFFIN S ET AL. (2014). Strategies to prevent catheter- associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 35(5), 464-479. doi:10.1086/675718

- CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL (2013). April 2013 CDC/NHSN protocol corrections,clarification, and additions. Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf - MOHAJER M & DAROUICHE R (2013). Prevention and treatment of urinary catheter-associated infections. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 15(2), 116-123.

- REBMANN T & GREENE L (2010). Preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: An executive summary of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc, elimination guide. American Journal of Infection Control, 38(8), 644-646.

- INSTITUTE FOR HEALTHCARE IMPROVEMENT (2011). How to guide: Prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/Topics/CAUTI/Pages/default.aspx

- GOULD C., UMSCHEID C, AGARWAL R, ET AL. (2009). Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Retrieved from

www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/cauti/cautiguideline2009final.pdf - BURTON D, EDWARDS J, SRINIVASAN A ET AL. (2011). Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adult intensive care units – United States, 1990–2007. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 32(8), 748-756

- CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL (2015). Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infection and other urinary system infection events. Retrieved from

www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/7pscCAUTIcurrent.pdf - CHENOWETH C & SAINT S (2013). Preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Clinics, 29(1), 19-32 doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2012.10.005

- TRAUTNER B & DAROUICHE R (2004). Role of biofilm in catheter-associated urinary tract infection. American Journal of Infection Control, 32, 177-183.

- NIKOLAEV Y, & PLAKUNOV A (2007). Biofilm -“City of microbes” or an analogue of multicellular organisms? Microbiology, 76(2), 125-138.

- KING C, GARCIA ALVAREZ L, HOLMES A ET AL. (2012). Risk factors for healthcare-associated urinary tract infection and their applications in surveillance using hospital administrative data: a systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection, 82, 219-226.

- BERNARD M, HUNTER K & MOORE K (2012). A review of strategies to decrease the duration of indwelling urethral catheters and potentially reduce the incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Urologic Nursing, 32(1), 29-37.

- TITSWORTH W, HESTER J, CORREIA T ET AL. (2012). Reduction of catheter-associated urinary tract infections among patients in a neurological intensive care unit: A single institution’s success. Journal of Neurosurgery, 116(4), 911-920.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3171/2011.11.JNS11974 - MURPHY C, FADER M & PRIETO J (2013). Interventions to minimise the initial use of indwelling urinary catheters in acute care: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 1-10.

- AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND UROLOGICAL NURSES SOCIETY CATHETERISATION GUIDELINE WORKING PARTY (2013). Catheterisation Clinical Guidelines. ANZUNS, Victoria.

www.anzuns.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ANZUNS-Guidelines_Catheterisation-Clinical-Guidelines.pdf - BARBADORO P, LABRICCIOSA F, RECANATINI C, ET AL. (2015). Catheter-associated urinary tract infection: Role of the setting of catheter insertion. American Journal of Infection Control, 43(7), 707-710.

- HOOTON T, BRADLEY S, CARDENAS D ET AL. (2010). Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 international clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 50(5),625-663. doi:10.1086/650482

- PLATT R, MURDOCK B, FRANK POLK B, & ROSNER B (1983). Reduction of mortality associated with nosocomial urinary tract infection. The Lancet, 321(8330), 893-897. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(83)91327-2

- WENZLER-RÖTTELE, DETTENKOFER, SCHMIDT-EISENLOHR ET AL. (2006). Comparison in a laboratory model between the performance of a urinary closed system bag with double non-return valve and that of a single valve system. Infection, 34(4), 214-218.

- KUBILAY Z, LAYON A, KUBILAY Z ET AL. (2013). What we don’t know may hurt us: Urinary drainage system tubing coils and CAUTIs – A prospective quality study. American Journal of Infection Control, 41(12),1278-1280. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.06.009

- MAKI D, & TAMBYAH P (2001). Engineering out the risk for infection with urinary catheters. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 7(2), 342.

This learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council competencies 1.4, 1.5, 2.1, 2.8, 3.1, 3.2 & 3.3.

Learning outcomes

- increase your knowledge of novel psychoactive substances (NPS) and how they affect mental health

- identify potential physical health and mental health risks resulting from NPS use for clients in your area of nursing

- increase your understanding of co-existing substance use and mental health problems and some approaches to managing clients that misuse substances like NPS.

Introduction

Novel psychoactive substances (NPS) or the so-called ‘legal highs’ are emerging rapidly worldwide, as are concerns about NPS abuse.

NPS have been a growing trend over the past decade for a number of reasons, including difficulties detecting them in routine urine drug screens, legal loopholes, easy access through the internet and low cost1.

Labelling these drugs as ‘herbal highs’ or ‘legal highs’ is misleading as there is nothing natural about these synthetic and untested drugs and also currently none of them are legal in New Zealand2. But there has been an explosion in numbers of NPS worldwide with the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) reporting this year that it is now monitoring 560 NPS and 98 new substances that were reported for the first in 2015 and 101 in 20143.

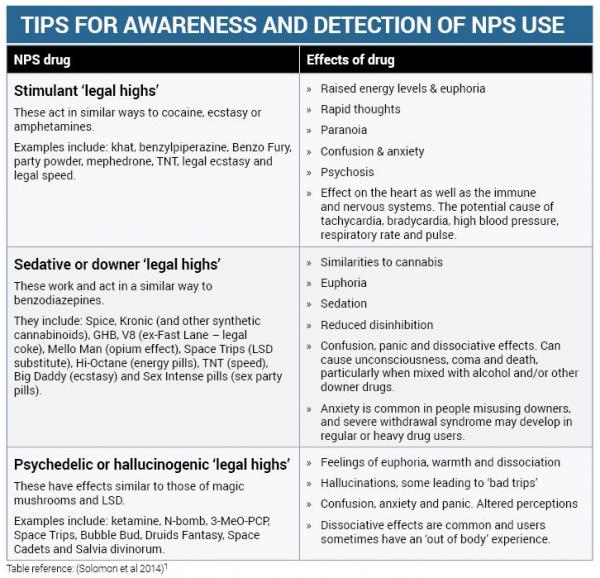

There are several typical categories of NPS drugs including synthetic cathinones (e.g. mephedrone and MDPV), plant-based NPS (e.g. khat and salvia divinorum), synthetic cannabinoids (e.g ‘Spice’, ‘Kronic’ and ‘K2’), and ‘party’ drugs like benzylpiperazine (BZP).

Synthetic drugs can be taken through insufflation (snorting), oral ingestion and rectal insertion, as well as being taken intravenously, intramuscularly and subcutaneously.